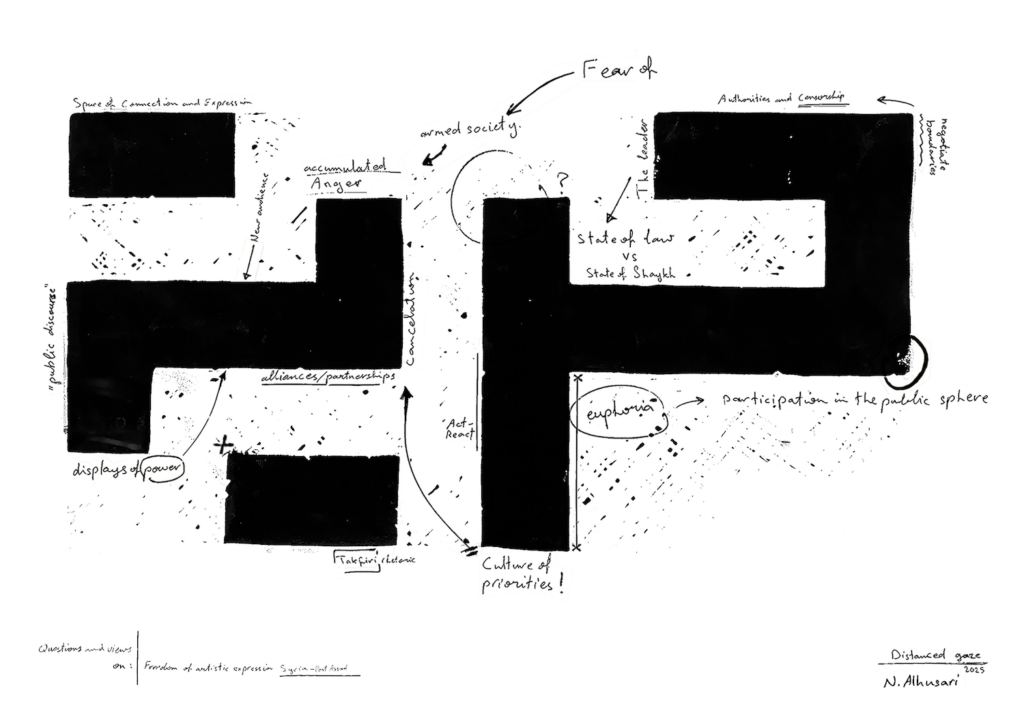

Syria post-Assad: Questions and views on freedom of artistic expression

by Nawar Alhusari

Introduction

Over a year has passed since the collapse of the Syrian regime, a regime whose name had been fused with that of the country for more than half a century. On 8 December 2024, what seemed like an unbelievable rupture in the lives of all Syrians was, in fact, a decisive shift in the logic of power that had shaped their consciousness for decades — a profound change in how individuals understood themselves and, more importantly, their relationship to authority. In those early morning hours, Syrians were left face-to-face with what Foucault calls the “mechanics of power”: the minute details embedded in everyday life that structure their movement, behavior, and interaction — and that invited a renewed exploration of their relationships with others in the brief void left by a repressive apparatus whose figurehead and consolidated power for more than fifty years.

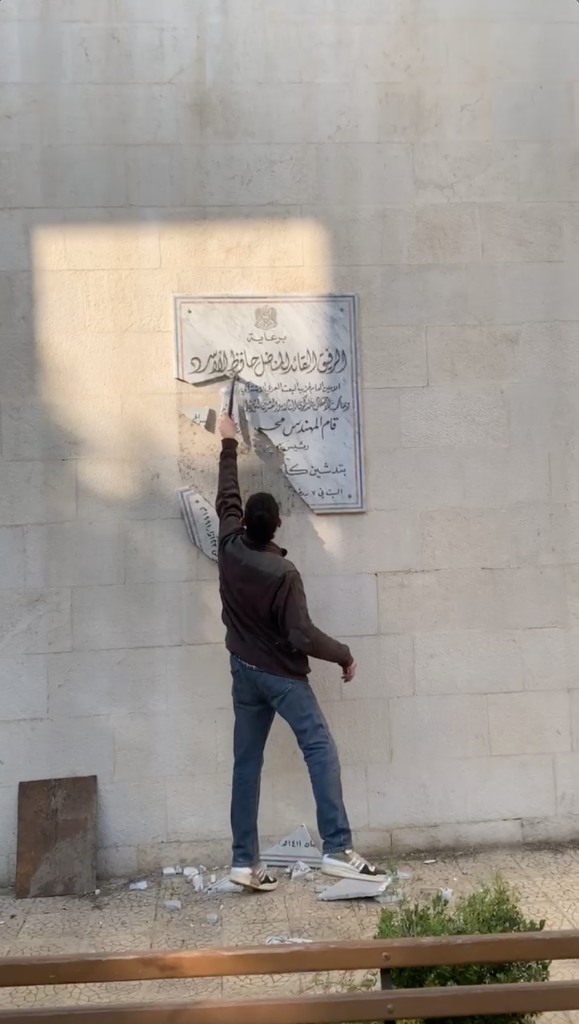

As a Syrian who was born and lived most of his life under that power, and who witnessed its fall from afar, it seems obvious to me how the former regime transformed everything in the country, every material and cognitive space, into their exclusive property with the leader’s images, statues, ideas, and slogans of loyalty and glorification. Every element of the public sphere—visual, architectural, and linguistic—had been mobilized as a tool and embodiment of the regime’s discourse, asserting the correctness of the singular, dominant vision of the leader while suppressing any dissenting voice. All of this remained an undeniable reality for Syrians until Assad and his discourse withdrew, and until — however briefly — the authority of silencing, surveillance, and fear receded.

The hours and days that followed this improbable shift formed the first real contact between Syrians and their public space: with the street, the square, the place — with the details of daily life inside a geography that had suddenly slipped from the grasp of state authority. Describing a scene from the historic Rawda Café in Damascus, a friend who works as a field journalist said to me, “In the first week the noise in the café was louder than you can imagine. Everyone was talking, participating. Each table felt like a political discussion circle that could merge with another table at any moment, expanding the debate. It was enough for someone to overhear something they liked — or disliked — from the next table to join the conversation immediately.”

Those first days and weeks amounted to a rediscovery of public space as a shared domain. Syrians, especially those inside the country, began to perceive new possibilities and boundaries as they moved through a space that had long been politically and socially produced. The public sphere, in which people regained their presence, became a reflection of identities and voices that had been marginalized and buried for decades. What we witnessed and heard in the squares and cafés at the time embodied this idea in practice. The space was no longer governed by an active machinery of domination — what remained of it were only the material remnants of cheap murals and colossal statues. It became, instead, a platform for symbolic and political engagement for the first time in decades, and people did not wait long before tearing down those statues — a symbolic reclamation of their right to appear, and a declaration of their right to exist.

Transformations in the New Power Discourse, and the Place of the Question of Artistic Freedom of Expression

With the arrival of the “liberators’” convoys to the capital, anyone observing noticed the tremendous shift in discourse and appearance from what most fighting groups had been known for throughout the long years of war. There was a conspicuous retreat from the harsh, rigid, and violent vocabulary of jihadist rhetoric. Fighters’ and commanders’ names and titles changed overnight, and even their clothing transformed: the robes and uniforms of “mujahideen” gradually disappeared, replaced by suits and ties. The new leadership, along with its media platforms — now speaking to all Syrians, and to the outside world as well — swiftly appropriated terms and expressions with a national, inclusive tone, derived from the early slogans and vocabulary of the revolution, blended with the language of statehood and responsibility. They presented themselves as the entity tasked with protecting state institutions and ensuring their continuity, and called on everyone to take part in building a new Syria: a free homeland for all.

As this surreal moment unfolded across Syrian life, anything felt possible: that Assad might disappear and his presence dissolve within hours — possible; that Syrians could witness live on-air raids of notorious prisons, turned to pilgrimages for tens of thousands searching for relatives and loved ones — possible; that Syrians might share, listen to one another, hear their own voices, and be heard amid all this ruin and all those years of silence — possible.

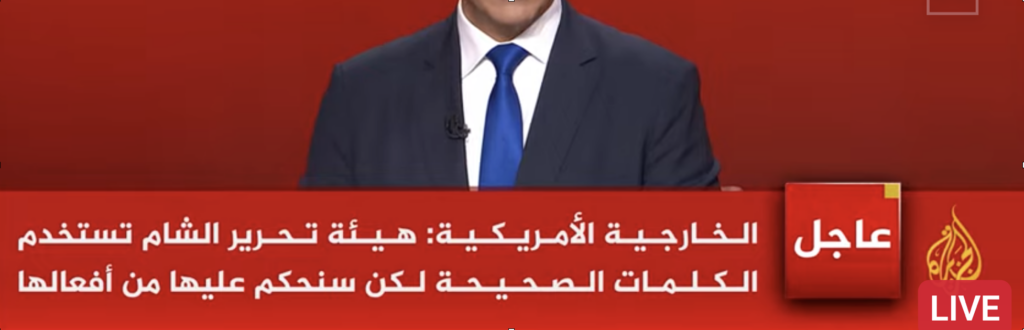

Even that a designated terrorist organization (HTS) whose discourse for years was rooted in takfiri ideology, and whose vision was an Islamic rule grounded in strict interpretations of scripture and rejection of any framework incompatible with its doctrine — could, overnight, present itself as an authority speaking on behalf of a state committed to law, international conventions, the rule of law, justice, equality, and human rights — this, too, suddenly seemed possible.

If all this were possible, could we then imagine a prominent place for artistic practice and culture as tools of recovery and as means of searching for a shared, representative identity for all Syrians after so much destruction? Could that be possible as well?

On December 30, 2024, the first broadcast interview Ahmed al-Shar’a gave, to an Arabic news Channel, from the presidential palace as the head of what was then called the “Transitional Administration” ended with the following exchange:

Interviewer: During my stay in Damascus, I attended a stand-up comedy show. Can Ahmed al- Shar’a attend a committed theatrical performance, even if it criticizes him?

Al-Shar’a: The truth is, I barely have time to sleep now. If I find some free time, I’d rather sleep than go to the theater.

Interviewer: So the answer is no?

Al-Shar’a: Honestly, I haven’t thought about this question. When I find the time to think about it, I will answer you.

On the ground today, several factors push my question about artistic freedom in Syria into a marginal position —dismissed by some as the product of a Syrian whose diasporic gaze has grown “orientalist,” or, as others say, as the concern of a “cute Sunni,” a label coined this year for Sunni individuals, including cultural workers and civil society actors, who rejected every form of violence and abuse seen over the past year. These labels and classifications reflect, to a large extent, the prevailing stereotype of

the intellectual, and of cultural work in public life. They are reinforced by exclusionary and restrictive practices adopted by actors aligned with the new authority, practices that also resonate with an official discourse in which culture in today’s Syria (as articulated by the current Minister of Culture) is framed as a matter of “priorities.” The minister — whose understanding of culture focuses on poetry, heritage, and linguistic eloquence — appears to be navigating a narrow space: acknowledging the value of culture in principle, yet presenting it through an approach tied to reclaiming the “authenticity” of Islamic and Arab society and reviving an identity he claims was lost due to the practices of the “Assad occupation regime.” This understanding of culture implicitly establishes a rupture with any intellectual or critical orientation that does not align with the transitional authority’s discourse. It also seeks to impose a reading of the moral and social values that supposedly express a singular Syrian society which is, in reality, religiously, ethnically, and linguistically diverse — and it reduces the social experience and its transformations into a univocal narrative. Moreover, it displays a dismissive attitude toward the social, critical, and communicative value of artistic and cultural practices — in all their diversity — as potential tools for opening channels of debate, difference, and exchange of perspectives.

Among the complicating factors is also the lack of clarity in institutional and legal mechanisms governing responsibilities, procedures, and the organizational structure through which creative and cultural work is supposed to be regulated inside the country. This makes any attempt to evaluate violations, permissions, licensing procedures, or even the forms of censorship that cultural institutions and practitioners may face extremely difficult to assess or measure.

Jumana Al-Yasiri, a cultural manager who I spoke with, notes in this context:

“There is no clear definition of art or culture in Syria today. For a year now, the authorities’ understanding of culture has been reduced to drama production, heritage, and religion. There is a clear trivialization of culture, and a very limited understanding of its forms, possible roles, and importance as a priority in public life. There is even confusion around the basic vocabulary and terminology describing cultural practices. This is something that cultural workers struggle with when speaking to officials while seeking support or approval.”

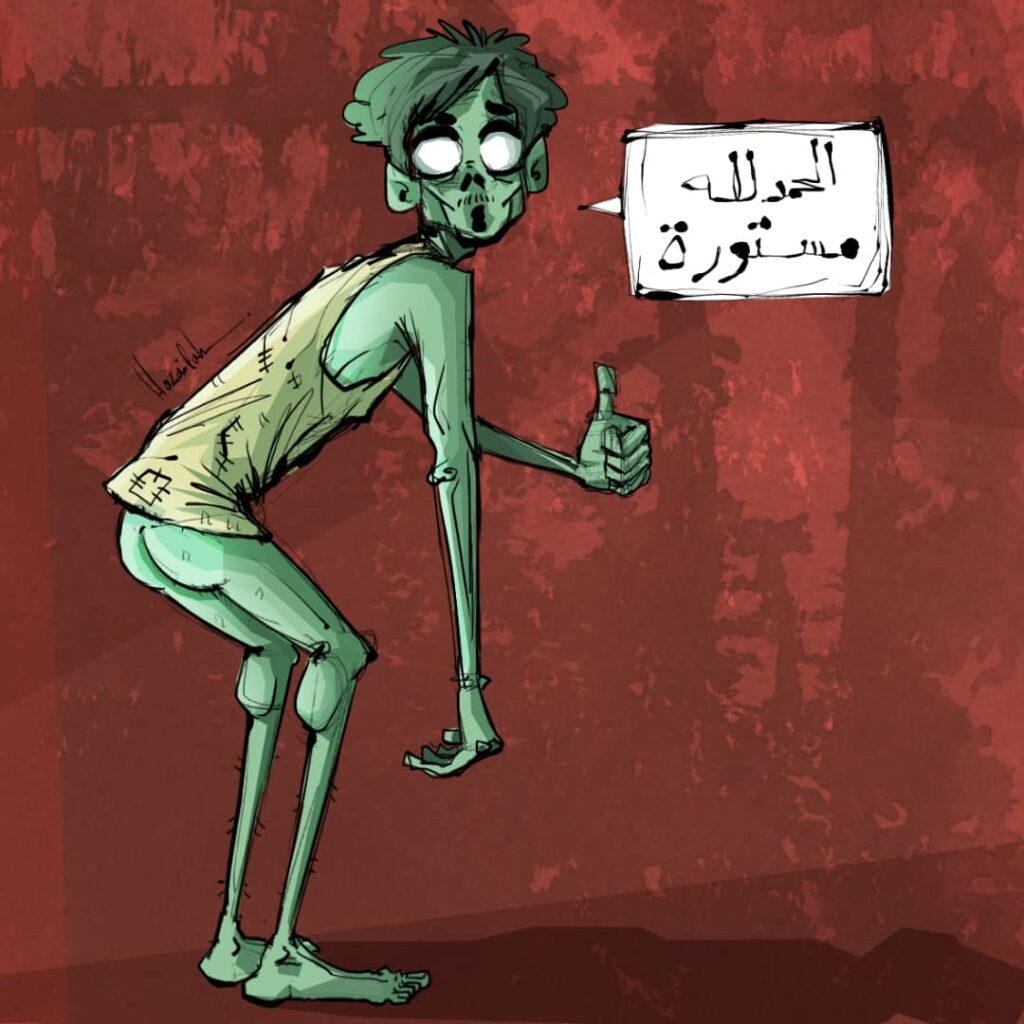

In a reality defined by uncertainty — affecting all aspects of life, especially basic needs — most Syrians inside the country today are preoccupied with survival, stability, and escape from economic, security, and social crises. Housing, water, electricity, food security — these are the needs that dominate daily life.

Syrian cartoonist Hozaifah Horieah, who lives in Damascus, describes this reality:

“The amount of daily burdens and tasks that drain a person’s time and energy — securing water and electricity, for example — all of these details limit one’s ability to think about artistic work and its challenges. This, for an artist as a member of society, is the first obstacle. That’s where the feeling begins that art has become a kind of luxury.”

As Syrians collectively renegotiate their relationship with shifting power structures — and to new forms, methods, and logics of control — how should we understand the relationship between the practitioner and the censor today? How does the Syrian artist or cultural worker navigate contemporary mechanisms of censorship and prohibitions? What is the current shape of expressive space, and where do the limits of censorship lie in the emerging Syria? And, more broadly, how can we make sense of the regulatory structures taking shape within the Syrian public sphere?

Ultimately, my question becomes: what can be done now — and in the future — to support artistic and cultural practices in Syria? What can their role and position be within the knot of transformations and challenges facing both society and the individual?

In my attempt to think through and find answers to these questions, I reached out to four individuals working in the Syrian cultural sector: practitioners, cultural actors, and artists, working independently as well as within cultural and artistic institutions and collectives. All of them have had experiences working on the ground in Syria after the fall of the regime. In addition to their observations of freedoms and censorship, at least three of the four participants have personally encountered incidents ranging from performance bans, attempted shutdowns, and restrictions, to cuts in support, cancelled shows, hate speech, and accusations of treason.

They are:

Jumana Al-Yasiri: cultural manager, consultant, and writer, born in Damascus and residing in France. In 2025 she returned to Damascus to lead and facilitate a consultative session with independent artists and cultural actors from various initiatives. She currently works on projects and initiatives aimed at supporting the independent cultural and artistic sector in Syria.

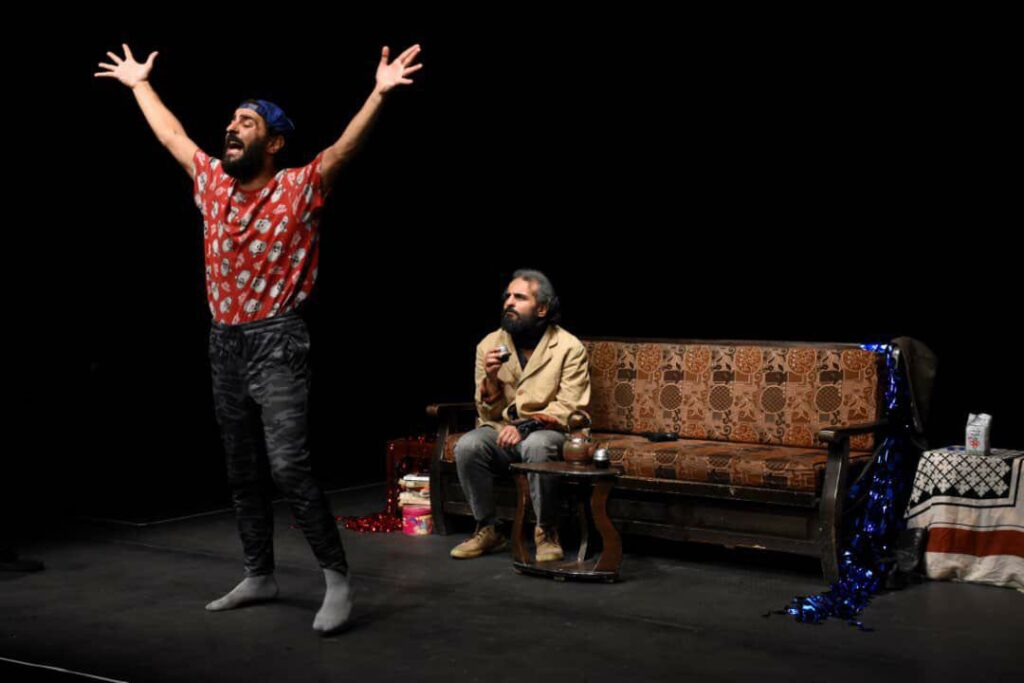

Mohammad Malas: Syrian actor and director living in France, working in Malas Twins Theatre alongside his brother Ahmad Malas. They founded the Room Theatre in Damascus before the Syrian revolution. They returned to Syria in 2025 and presented several performances and workshops before the project was halted following a dispute with the Syrian Ministry of Culture and its attempt to control their artistic content.

Sharif al-Homsi: Syrian stand-up comedian based in Damascus, founder of Styreia Comedy, the first stand-up comedy troupe in Syria, which began performing in late 2022. After the fall of the regime, the group launched its largest tour across Syria — only to be surprised by the cancellation of a show in Hama, followed by another cancellation in Mhardeh, justified by claims regarding the conservative nature of the local community and the need to regulate inappropriate content.

Hozaifa Horieah: Syrian cartoonist based in Damascus, whose work focuses on critiquing surrounding social realities. He collaborates with Madad Art Foundation on its artistic projects — either participating or helping organize. Earlier this year, the foundation faced an attempted shutdown by a man claiming official authority, who stormed the premises and demanded its closure on the grounds that it was affiliated with the previous regime and promoted practices allegedly incompatible with local values.

Inherited Fear and Its Impact on the Scene

When examining the state of artistic freedom of expression in Syria, fear emerges as one of the most influential forces shaping the individual’s capacity to act, to express, and to understand their own position within the limited space available today. This experience of fear is not confined to a direct relationship with political or religious authority, or an even combination of the two. Most social structures that an individual encounters, beginning with family and extending through their neighborhood, school, and workplace, contain their own forms of authority. These structures often enforce surveillance-like behavior and strict rules that govern conduct and expression, either out of deeply rooted conviction or out of concern for potential consequences that might affect the individual or the community around them.

Hozaifah Horieah, speaks about fear as a hereditary force that dominates the experience of Syrian artists. He says: “Fear, for us as Syrians, is always present and even inherited. Like any acquired genetic trait, our fear is passed down. We have lived under a repressive authority for sixty years. My grandfather passed fear to my father, and my father passed it to me, and so it continues.”

Hozaifah adds a personal example from the years when he experimented with drawing Assad: “I used to try sketching him in a satirical way, but I could never forget a drawing inside a notebook or on a loose sheet, even in my own room. Anyone could find it during a routine security raid. You know what that means and what could happen to you if you draw ‘the god’ in a mocking form. Each time I drew him, I made sure to tear the paper into very tiny pieces.”

Generations of fear created by the authoritarian regime, and the logic of power it represents, had become embedded inside every Syrian in the form of an internal censor, making free expression a difficult act, burdened by the awareness of possible consequences for crossing taboos or red lines. These consequences included repression, arrest, torture, disappearance, or even death. Silence within such a landscape, filled with security branches and torture facilities, is not necessarily a sign of approval or support for the regime.

Syrian artists found themselves confronting this fear constantly. Over time, they developed professional and artistic strategies, along with coping mechanisms, within an environment that provided very limited space for independent artistic activity, particularly practices that did not align with the dominant cultural direction. One example can be seen in the experience of the Malas brothers, known for their experimental theater work and specifically the “Room Theater” project during the years before the uprising. Later, after taking a public stance against the regime and leaving Syria to settle in France, Mohammad Malas reflects on the role of fear and the unstable relationship with censorship in Syria, and how it shaped their initial artistic experience in France.

He recounts an incident while preparing their first theater text in French: “After I finished writing the text in French and it became ready for performance, the first question I asked a French friend was: How can I get approval for the script? He genuinely could not understand the question. I explained that we needed official approval in order to perform it. He truly did not grasp what script approval meant, and he told me that my relationship is only with the theater itself. No one interferes with your text.”

Experiences like this open a path for extensive studies on how fear of expression persists, how it travels with the artist into exile, and how it shapes the artistic experience of Syrians long after leaving the original context.

The role of self-censorship for the artist or cultural practitioner does not end with fear of political authority or with choosing which topics to address. After the fall of the regime, another factor emerged as a defining element of the current Syrian reality, namely the role of social censorship. This appears most visibly through comments and reactions on social media, which have become a central part of the environment described by every person interviewed for this article.

For example, Hozaifah recalls several incidents that followed the publication of his drawings on Instagram. He describes the insults and threats he received, even though the drawings themselves addressed a social issue that criticized the polarized atmosphere and attempted to redirect attention to the harsh living conditions experienced by people in the city.

Within the relatively new field of stand-up comedy in the Syrian artistic scene, fear takes on another shape. The concern is no longer limited to the figure of the leader or the army, as it was in previous decades. The anxiety now comes from a society exhausted by war and armed with accumulated anger. Sharief Homsi, founder of Styria Comedy, explains this situation:

“We understand that there are deep wounds that remain open. The unrestrained spread of weapons can lead to dangerous consequences on the ground.”

For this reason, even a joke can escalate into a major confrontation. The performer is placed before a difficult equation: they want to speak openly about everything they observe in the new reality, using their own satirical lens; yet they face the risk that “a joke about a local accent may be interpreted as an attack on a community or region that suffered bombing and siege, or as disregard for their pain.”

Although many practitioners have a sense of unprecedented space for expression after the fall, there is a shared understanding that this freedom remains conditional. There is also fear that these conditions will persist or even grow stricter. Sharief recalls statements from officials and armed personnel: “They told us to say whatever we want on stage, but not to film or post controversial clips on social media, explaining that it is difficult to control an angry, armed society even today.”

This reveals how the digital sphere has shifted from a space of connection and expression into an additional site of surveillance, dominated by language of accusation, threats, and defamation. It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to regulate this environment in the absence of laws capable of addressing such forms of harassment.

This lack of regulation in online spaces has resulted in the wide spread of hate speech and harassment online, exerting significant influence over Syrian public debate. Creators, discussing their rapidly changing reality, find themselves exposed to an open arena filled with incitement, between takfiri-Excommunicationist rhetoric and treason-accusing rhetoric, with no legal frameworks that can restrain this escalation. Each incident of polarization or controversy is treated as an individual matter, with little consideration for the role of state institutions in delineating and regulating the boundaries of expression, action, and artistic practice.

In discussing the exclusionary discourse that has come to dominate public life—emerging whenever an event or statement diverges from the rhetoric of the new authorities or touches its taboos—Jumana drew attention during our interview to what I would call a controversial example from the Syrian sphere, one she had followed closely this year. It concerns a famous Syrian actress who had defended the Assad regime both before and after its fall, and as a consequence, was stripped of her membership in the Syrian Artists’ Syndicate.

The actress in question had gone to extraordinary lengths in a provocative denial of the regime’s crimes or the involvement of the head of the regime in any of them- crimes whose reality is known to every Syrian regardless of differing interpretations and histories of opposition to them. Her statements, made in a personal capacity on television and on social media, resulted in what Jumana described as a study in what she calls the emergence of a new “Syrian cancel culture.”

Even though this example is deeply contentious for many Syrians—and legally fraught, given that the actress’s statements preceded the constitutional declaration criminalizing the denial of war crimes committed by the Assad regime—it remains revealing. Together with other cases, perhaps less extreme, it illuminates two important dimensions directly relevant to this research.

The first is the absence of a clear understanding of freedom of expression as a right belonging to any citizen, versus freedom of expression solely within an artistic practice or cultural output. The fear of censorship here exceeds direct institutional or official oversight of a cultural or creative act. Rather, it is becoming a fear of a generalized form of censorship—one that strips individuals or groups of their sense of autonomy. Artistic or creative practice can be understood precisely as a platform for such capacity to act, especially for artists and cultural practitioners whose work relies on direct communicative engagement with audiences and on presenting critical perspectives on contentious social issues.

Meredith D. Clark argues that cancellation “is itself an expression of agency: a choice to withdraw one’s attention from a person or thing whose values, (behaviors), or speech are so offensive that we no longer wish to honor them with our presence, time, or money.” (Clark 2020).

Yet, for many, the scene in Syria today resembles a gradual takeover of the public sphere and of the fragile agency of expression—a sense of freedom that was reborn the day the regime fell. It was this same need and search for agency that, after decades of repression, helped give rise to the Syrian uprising of 2011: an act of refusal and civil disobedience through which younger generations and marginalized communities—whose voices and capacity to express or object had been steadily eroded—sought to reclaim their lost capacity, caught between an internal patriarchal authority of clan elder or family head on one side, and the Leader, his army, and his absolute power on the other.

While the transitional authority’s discourse promises a coming era of freedom, dignity, and vitality, the sense of agency, or the feeling of regaining it, among supporters appears to draw from a mixture of fear and anger, coupled with a heightened sense of grievance and hypersensitivity toward the “other.” This resurfaces whenever anything threatens to disturb the state of euphoria, spectacle, and awe produced by displays of power, the restoration of historical glory, and the celebratory rituals marking this past year. Such a reality extends far beyond a media statement made by a famous artist or actress. For most of the individuals I spoke with, this extends to evaluating artistic practices that hold critical value in their message, or those that introduce, through approach or discourse of this practices, opinions or ideas unfamiliar or unacceptable within a particular social environment.

This leads to the second aspect illuminated by the case Jumana mentioned previously: the cancel culture emerging today is a representation of a new de facto authority, a “symbolic power,” as John B. Thompson originally described it, and was later reframed within social media by Christian Fuchs. In other words, in the absence of structures that regulate justice, accountability, civil peace, and other foundational mechanisms, or amid a systematic marginalization of these mechanisms, despite their necessity for societal recovery and renewed social communication, this void becomes fertile ground for forms of community-driven censorship rooted in accumulated anger, monopolization of grievance and marginalization experienced under the former regime. Such mechanisms then claim legitimacy in passing judgment and exert influence over the decisions of authorities and institutions—institutions that, in turn, appear to rely on prevailing discourse and social-media sentiment as indicators of public mood, or even as tools for producing it.

The result is a digital sphere functioning as a substitute for absent representative and participatory structures—structures that remain entirely missing from the Syrian reality today, including any political sphere where Syrians can act collectively, or any long-term societal dialogue employing all possible tools for communication, representation, reconciliation, and reconstruction.

Before closing this fear chapter, when looking at its consequences from the position of practitioners, cultural workers, and artists—one last point emerges, rooted in the same chronic anxiety: fear’s transformation into a productive and active force. After the fall of the regime, Syrian practitioners and actors in the cultural and artistic fields appear to be gripped by an acute fear and sensitivity toward losing any space or platform for expression, practice, or production. This is a condition Hozaifah described when commenting on the attempted closure of the Madad Arts Initiative headquarters earlier this year—an incident he witnessed firsthand:

“There is fear and apprehension among many in the cultural field about losing the place of art, cultural institutions, and their roles in the country. It’s a defensive state: fear and urgency. We were stunned by the way so many people reacted when someone—angry as well—tried to shut down the Madad space less than a month after the fall of the regime, on the grounds that it was linked to the old one, which was slander. But what surprised us even more was how artists and media figures rallied around us, using their channels of communication with the new authorities and their visibility on social media to draw public attention to the issue. That wave of posts, calls, and appeals was the reason the security official responsible for Damascus at the time came personally, and why the authorities were keen to resolve the matter immediately, given its impact on the image of the new power—especially in that early phase.”

Incidents like this reveal the need for collective action driven by an awareness of the need to exert pressure and raise one’s voice, particularly in a political and social transformation of this scale. They also illustrates how individuals come to test a possible form of collective action: as a reaction to a threat targeting their position within society and their ability to practice and produce.

Fear is a form of knowledge, an understanding and awareness of the narrow space for expression and the possible consequences of crossing imposed boundaries. In this sense, the productive dimension of fear becomes a motivating power, pushing artists or performers to refine and develop their tools. Sharief Homsi explains:

“Before the fall of the regime, our awareness of the red lines—and the constant negotiation of a very tight space of what could and could not be said—was an important factor that sharpened our experience and improved the quality of the performances themselves: what we say, how, and when. Today, drawing on that past experience, we are negotiating the available expressive space more intelligently. We present material and content that can be interpreted in multiple ways, allowing us to maneuver and continue working…”

Expression is possible and present, but!

Like everyone I interviewed for this article, Mohammad Malas reflected on the current landscape after his and his brother Ahmad’s return to Syria: “We cannot deny that we can speak now—and a lot. Things are certainly better than before. But this is not thanks to the current government. The credit belongs to the revolution and the price that was paid for this.”

Indeed, the fact that I can write and publish this article today, mentioning my own name and the names of participants, many of whom still live inside Syria, speaks to the existence of a space in which such discussions can take place. But, this does not negate the depth of the challenges facing artists and practitioners, particularly regarding how to navigate the authorities, their many representatives, and the ambiguous nature of their own role within the new reality.

When speaking of freedom of expression in Syria today, one must emphasize that the legacy of fear discussed earlier, especially among cultural workers and artists, extends beyond the chronic fear of political authority (including the new one, given its documented history of violations). It also includes fear of losing the fragile agency regained after the fall of the regime: a reclaimed margin of expressive freedom secured through years of struggle and immense sacrifice during the revolution, whose earliest demand was freedom.

In my discussion with Jumana, she commented,“Through my visit to Damascus and all the conversations I had, I can say that everyone understands that silence is not an option now—from the taxi driver to the artist. They all agree that they cannot afford to be silent today. For many, they plan to continue speaking and working until they collide with the limits of the authorities and censorship.”

It is therefore a process of testing and experimentation between cultural actors and individuals on one side, and the new authorities and their censorship tools on the other, as a mutual attempt to understand one another and to negotiate boundaries on a seemingly case-by-case basis – especially since there is no clear framework for how the authorities understand culture or define it.

Anyone observing the history of those in power today, from their time in Idlib and other areas in what was known as the “liberated north” where they established a regional government called the “Syrian Salvation Government,” to their arrival in Damascus, can recognize that their approach to freedom of expression, culture, and arts differs fundamentally from that of the Assad era.

Under Assad (father and son) as in every Arab Nationalist Regime arrived to power between 50’s and 70’s of last century, the red lines were tied to a secular authoritarian structure— intertwined with military and security apparatuses, manifested in the sheer number of intelligence and interrogation offices and detention centers that permeated cities, public institutions, and the consciousness of the individual, producing an internalized censor. However, even in the context of that oppression, artistic and cultural practices were actually supported, indeed encouraged, in an effort to soften the regime’s harsh image. But the content always had to be tightly controlled, ensuring that cultural production remained, to a significant extent, a tool that reinforced the dominant narrative domestically and internationally.

James Davison Hunter, a sociologist and author of the 1990s culture wars thesis mapped these contours of power perfectly, declaring that “public discourse is a discourse of elites. That is where you find this conflict at its most incendiary The power of culture is the power to define reality, the power to frame the debate, and that power resides among the elites.”

In the Syrian context, the problem was that the authoritarian structure—through its red lines— distanced much of the cultural elite, or at least their discourse, from engaging critically with the lived realities of marginalized communities outside major cities. These communities formed the social majority, whether in religious affiliation or socioeconomic status. Cultural production, with some exceptions, fell into the trap of generating knowledge that lacked a clear political and social role, constrained by the very boundaries that prevented it from addressing deeper societal issues or recounting the long history of political tyranny and corruption, or critiquing the hybrid urban-rural structures and the enforced “national unity” discourse.

Further fracturing the arts’ power to influence the public, independent cultural and artistic work was in fact unable to establish active communication or stimulate action beyond urban centers — especially outside the capital Damascus, which functioned as the primary hub of cultural and artistic production.

The Compendium — Syria: Profile on Cultural Policy (2014) published by Al-Mawred Al-Thaqafi (Culture Resource) Organization highlights this centralization: Syrian cultural policy was traditionally centralized and controlling, leaving independent artists without support structures in rural or less urbanized regions, limiting the reach of artistic work.

Turning back to the current authorities, their ideological foundation —shaped by extremist religious discourse and intertwined with communities that endured profound marginalization during the Assad regime—has played a significant role in shaping a distinctly different approach to freedom of expression, now framed as a “reclaimed” right following the fall of the Assad regime. However, this same ideological foundation also plays a large role in shaping the problematic stance on the role of art and culture, and even on the very definitions of these fields within their vision for Syria’s future. It informs their problematic stance on the role of art and culture, and even on the very definitions of these fields within their vision for Syria’s future.

Today, following a year of incidents of banned events, obstructed performances, and artistic silencing — a year which motivated this research — the question naturally arises: What boundaries on expression and censorship are the new authorities now establishing, even as they claim, at home and abroad, to embody a revolution that sought to topple a tyrant and reclaim freedom and dignity?

Interrogating these boundaries might offer us an insight into the dominant discourse being established in the public sphere, and how it is being enforced. Sharief notes: “Today we can speak and express ourselves. And those who contacted us from the new authorities stressed that they do not intend to create an idol or a sacred figure who cannot be criticized. But, they also had boundaries that quickly emerged: references to God, divine attributes, and core religious themes. We were told to be cautious with topics that are sensitive within society.”

What Sharief describes about shifting boundaries and the role of religion largely reflects the official discourse of the current authorities: upon entering Damascus, they adopted the very early discourse of the revolution, emphasizing the relationship between “state” and citizen, rejecting the sanctification of political figures, and affirming freedom of critique. Yet what followed included reminders of “obvious boundaries,” and imposing of multiple vague and expansively enforceable restrictions. Phrases like “socially sensitive topics,” “proper language,” or “threats to the family structure” rely on the premise that the state’s role is to protect moral values and cultural identity, according to its own interpretation.

Mohammad Malas remarks: “In terms of censorship, the distance between us and the rest of the world remains immense. A political censorship problem could cost you your life. And when it comes to religious censorship, the accusation of disbelief is raised immediately.”

The threat of “disbelief,” in today’s Syria, reflects a broader societal stance toward the arts and cultural production. Between freedom of personal opinion, which individuals feel they possess after the regime’s fall, and artistic freedom, which should logically expand within any context of broader civil liberties, artists find themselves confronting layers of social and political censorship. Their artistic autonomy is scrutinized under a framework justified by the supposed guardianship of revolutionary legitimacy, religious values, family norms, and public morality, values the new authorities claim were long marginalized, and which they now consider it their duty to restore.

The New Guardians of the Sacred

The positions expressed by the participants I interviewed, along with my own attempts to grasp the shifting landscape, reflect scenes from the country’s ongoing transitional phase. The reality of artistic freedom is no exception to these transformations. What once was a centralized authority built on fear — anchored in its security apparatus and in a singular “center” presented as the nation’s shield against enemies and conspiracies, as under the Assad regime — has shifted toward a multi-headed system of censorship that grounds its legitimacy in protecting the country’s supposedly “authentic” identity restored by the revolution and in defending religious and social “sanctities” claimed to have been suppressed under the former regime.

What I described earlier as uncertainty in this new -hopefully transitional- era of censorship lies in the overwhelming multiplicity of actors and the diversity of their tools, ranging from silencing, banning, and canceling to verbal aggression and explicit threats of accountability or retaliation. In discussing today’s power structure, Malas sees that: “The state today is two states: a state that believes in the law, and a state that believes in the authority of the shaykh… A minor employee can halt a performance because it contradicts religion, even if the state itself might have no objection.”

Thus, artists now face a multi-faceted authority. What was once banning and punishing through intelligence networks and coercive practices—has receded with the collapse of that regime, only to be replaced by a new discourse whose proponents install themselves as the new guardians of identity and its sanctities.

With this drift toward unrestrained and diffused decision-making, the problem does not seem any longer simply the act of censorship itself, but the impossibility of knowing who even holds the authority to censor.

This may be characteristic of many transitional phases, yet the more fair question today is whether we should understand this situation as an inevitable byproduct of transition of recovery and justice, or as a deliberate operational mode designed to scatter attention and undermine the ability to track accountability among those active in this sphere.

In describing the censorship incident faced by Stereya Comedy, Sharief explained during the interview I conducted with him—amid their largest tour since the group was founded, across several Syrian provinces: “During our current tour, while preparing for the performance in Hama, the organizer informed us that a report had accused us of supporting homosexuality, and that holding the show would be difficult. After reviewing the report and contacting officials in Hama, the issue turned out not to be connected to LGBTQ support, but to the topics we address, claiming we use profanity in our shows and promote ideas that could ‘undermine the family structure.’ Within this climate, some of us reacted to the decision; one team member was a bit sharp in his criticism on social media. Our response led to the ban being extended from Hama to another city in Hama’s countryside: Mhardeh. Later, we contacted security officials, who told us that the ban was unrelated to all previous reasons and was instead based on prior reports and recommendation from the Ministry of Culture prohibiting the use of ministry-affiliated theaters or cultural centers for some of our shows. They said the report was taken seriously because of Hama’s conservative social fabric. Keep in mind there were 400 reservations for the show in Hama… And we’re not entering people’s homes or even performing in public spaces; people pay to attend because they want to…”

All the cases share the same lack of clarity and absence of transparency regarding the reasons for banning, cancelling, or shutting down events, as well as the refusal of any specific authority to assume responsibility for these decisions—or to clearly articulate the grounds for such measures in

public. Most of the recorded incidents involved shifting justifications, obfuscation, and evasiveness toward the official narrative of “freedoms” and “coexistence” the authorities promote outwardly.

Although many interviewees acknowledged the goodwill of certain officials who genuinely try to offer support, these individuals appear, within the actual power dynamic between artists and the real censors, more like intermediaries or translators between artists or cultural actors and other actors within or adjacent to the state, or even segments of its agitated audience, now self-appointed representatives of sacred values whom they believe independent cultural and artistic practices threaten.

Another clear example is the case of al-Kindi Cinema in Damascus which came up in nearly every interview. As it had stirred significant controversy and raised genuine fears about the place of culture and the arts in the “new Syria.” The Damascus Directorate of Religious Endowments (part of the Ministry of Religious Endowments- Awqaf) had announced the termination of al-Kindi Cinema’s contract, citing the need to “rehabilitate the property” and transform it into a cultural center “from which the light of knowledge would shine upon Syria’s youth.” After a wave of criticism, a picket, and extensive discussion across social media platforms, the newly appointed Director of the General Organisation for Cinema appeared to confirm that al-Kindi Cinema would reopen following an agreement with the Ministry of Endowments. Yet field reports later showed that the ministry had ultimately converted the cinema into a cultural center under its control, contradicting the director’s statements.

Independent filmmakers issued a petition reminding the public that al-Kindi was a cultural and historical landmark forming part of Syria’s visual memory. They stressed that this venue, long a witness to the evolution of cinema in the country—represented a space for culture, dialogue, and experimentation, and that protecting it was a collective responsibility linked to the history of Syrian cinema and the right of citizens to a shared cultural sphere.

Stepping back, it appears evident to anyone concerned about freedom of expression—and artistic and cultural freedoms in particular—that an erratic and unstructured system is governing the cultural and artistic sector in Syria. Behind it stands a power resembling a parallel or “deep state,”as Jumana described it, ultimately wielding decisive influence over cultural policy and decision-making. This is perhaps what Mohammad Malas meant by the “State of the Shaykh”: the convergence across cases where censorship did not exclusively originate from any official state or regulatory body tasked with organizing cultural work and cultivating a constructive relationship between practitioners and state institutions in service of society. Instead, decisions seem to be taken from various individuals—official or “independent” figures known only within narrow circles of power, whose directives no ministry or censorship committee can override.

As for the Ministry of Culture, reactions to its conduct range from bewilderment to disappointment. The ministry, expected by artists, practitioners, and institutions to act as a guarantor of their work and a supporter of cultural and creative activity, essential to any societal recovery process, has not stepped into the role many hoped for. One might have expected it to explore, alongside practitioners, the potential of the cultural sector and artistic practices as tools for truth-telling, community reconciliation, and social engagement (such as the South African post-apartheid experiences, which offer compelling models for re-imagining collective narratives and shared spaces in the wake of fractured histories). This and many other experiences can be taken as models relevant in the Syrian context, which has endured years of war, social fragmentation, and mutually hostile discourses across divided communities.

Instead, the ministry has restricted its support to projects documenting stories of Syrians who resisted the former regime, while avoiding projects and activities that would acknowledge or

discuss abuses committed by other actors involved, past and present, particularly those aligned with current authorities. It has also neglected critical approaches of artistic practices, as though pursuing, in its minister “culture of priorities”, a strategy to construct a one dominant narrative for one represented group, absorbing or excluding all others.

The Ministry’s quiet withdrawal of support, revealed only afterward to have been conditional, for the touring performances and workshops organized and conducted by the Malas twins across several provinces offered a telling illustration of this dynamic. Official backing for their work was abruptly suspended following the twins’ public stance (on Facebook) against the authorities and the violence and sectarian rhetoric propagated by their affiliated fighters. This position was after the bloody events in AlSuwayda, the predominantly Druze city, where hundreds of civilians were killed— echoing earlier, eerily similar atrocities in the coastal regions, home to Alawite-majority communities.

Mohammad Malas recounts that experience: “It seems they thought that after thirteen years of revolution and displacement, we would return as the Malas twins to stage a celebratory play announcing the victory of the revolution—honoring the martyr’s mother, weeping over ruins, using visual effects to stir emotion, and ending with revolutionary chants that once dominated the streets after the regime’s fall. That is not the task of theater… and not the task of the Malas brothers’ theater. Because I care about this country and respect it, I speak about its mistakes. Because I love this country, I added a line in one scene saying that the actual ‘kuffar-infidels’ are those who threw doctors from balconies in one of the most horrific scenes imaginable we saw in AlSuwayda. We did not endure thirteen years of revolution so that they could enter AlSuwayda and the coast and commit these massacres while we stand by as spectators.”

The open question

Between chronic fear, the emerging boundaries of expression, the new guardians of identity, and the rhetoric taking shape, the Syrian artist and practitioner — inside and outside the country — finds themselves facing serious questions. In this shifting and uncertain environment, artists must consider not only how they practice, but also the factors that shape their methods, subject matter, and audiences — including the media and technologies they employ, which are themselves constrained by economic conditions and social norms. The result is a tension between cultural or artistic production that can market itself in this reality as simplified entertainment — catching attention with familiar language to pass content quietly within the limits of what is possible — and committed political art as an activist social practice that seeks its space at the margins of censorship, attempting to push boundaries, create fissures of doubt and provocation, and prompt self-reflection within dominant or emerging discourses, all while recognizing potential consequences and continually searching for tools and mechanisms to cope with them. As artist and activist Tania Bruguera shared with the 2025 “The Art* of Defending Artists 3.0” Avant-Garde Lawyers capacity building programme, “There is art that springs from existing political situation and speaks about them, and there is art that produces or opens the way toward a political situation… The task of political art is not to change politics or society single- handedly, but to open a path and share ideas that could lead to such change.”

Between these two conceptions and under the weight of all influencing factors, a kind of consensus emerges: not to be silent or to acquiesce to a reality being imposed again over time; to continue working, producing, and acting in every possible direction; to support experimentation and divergent proposals; and to benefit from all experiences and potentials inside and outside the country through alliances and cooperation to consolidate some capacity for resistance, negotiation, and participation in the public sphere — a sphere that Syrians regained materially and morally when the tyrant fell.

Syrians cannot again wait in silence for decades, hoping to test the autonomy that was stripped away or to test a public space that was lost under the Assad regime. Nor can they wait as long as it may take for a Syrian “transitional” president to finally answer, with clarity, the question posed to him in his first days in the presidential palace: could he attend a —committed — theatrical performance, even if it were critical of him?

RECOMMENDATIONS

On seeking partners- Who, For What, and How?

The dose of freedom Syrians wrested, and which endures to this day, allows them (us) to speak out, relatively loudly, and to debate what is happening and what can be done. This, however, does not erase the facts on the ground. The first anniversary of the regime’s fall also marked a year filled by many concerning violations, exclusionary and censorial practices aimed at cultural and artistic sectors. Artistic practices and approaches faced censorship on multiple bases, including practices that explored free communication and exchange with other Syrians, solidarity with social problems, deconstruction of dominant discourses, and critique of the roles of ruling authorities and their agents. In whatever form, these practices as many would argue, remain at the core of art’s role and the catalyst of cultural practices in Syria’s fraught context.

Against this background, all participants in my research emphasized the need to initiate robust, cross-border spaces of communication, cooperation, and support between Syrian practitioners, artists, and collectives. Those based inside Syria, on the one hand, possess the lived experience and practical know-how of available modes of action, the possibilities of maneuvering on the ground, and dealing with logistical, censorial, and security challenges—elements that, I would argue here, are foundational to the artistic identity, and to Syrian cultural production more broadly. Syrians in exile, on the other hand, or those whose experiences have been shaped by displacement and diasporic experiences, can contribute the expertise they have developed through engagement with different institutional structures and legal frameworks in their host societies, as well as through experimenting with broader approaches and expanded roles for artistic and cultural practices (their tools, spaces, and modes of communication and engagement with audiences and communities).

Such partnerships or alliances also hold the potential to reconnect Syria’s independent cultural scene with other cultural and artistic initiatives capable of advocacy and support.

Rather than offering definitive answers to our open questions, some of which are not even directed to us, the following recommendations are proposed as a continuation of the inquiry itself, and the forms of cooperation and engagement the practitioners envisioned between inside and outside the country, I organised their perspective into three interconnected frameworks:

Practical and scholarly cooperation

Hozaifah, for example, spoke about his hopes for collaboration and about the expectations inside Syria that partners abroad will help activate the cultural scene and break the long-standing monopoly over artistic production.

“We need assistance,” he said. “We wait for the return of practitioners and organizations that have deepened their studies or practical experience abroad — individuals and institutions — to activate artistic practices and exchange new methods and how to adapt and invest them so that artistic and cultural production genuinely can communicate, and participate in the recovery process. I hope new partnerships and initiatives involving expertise and institutions will help break the artistic monopoly that has long existed in Syria. For visual arts there are a limited number of galleries in Damascus that control what is produced and the whole market of Art.”

He also emphasized the urgent need for spaces where artistic action and experimentation can take place.

Financial and logistical support

Hozaifah’s call for venues and financial resources intersects with what Sharief Homsi proposed, offering concrete solutions from within Damascus:

“There are 1,300 never-used underground shelters in Damascus; we could get access to such a place, a shelter where we could settle and share a dedicated space for artists, photographers and other practitioners…”

Mohammad Malas, meanwhile, highlighted the dangers of relying on state funding, linking the cancellation of shows to support they had received from the Ministry of Culture:

“I believe the job of NGOs and independent actors today is to provide alternative funding and other support means for individuals… When we worked within the room,” he said, referring to their project Theatre of the Room, “we were free. But when the authorities contacted us through the Ministry of Culture to hold shows and workshops, at the first disagreement they started saying they supported us and that we must not speak against them, and that is how the cancellations ultimately occurred.”

Advocacy and legal support

The legal context governing cultural and artistic work in Syria remains one of the thorniest and most complex issues, shaped by decades of authoritarian rule in which law functioned primarily as a tool of control. This framework therefore includes two dimensions:

- The current legal structure, which is a hybrid of the old regime’s statutes and new decrees issued by today’s authorities. Some laws are enforced selectively, while extra-legal policies are applied whenever convenient. Sharif notes, for example, that:

“Stand-up comedy is still not officially classified as a recognized cultural or artistic practice in Syria; situating it within theatrical arts means in the current laws that we must submit ready texts to obtain approvals for performance, which contradicts improvisation and real-time interaction with audiences — the essence of this practice.”

- The absence of institutions capable of offering legal advocacy or protection. None of those interviewed mentioned any legal body that could help resolve disputes, guarantee rights after cancellations, or hold authorities accountable — unsurprising in a country emerging from authoritarian rule with no tradition of genuine civic partnerships.

Jumana Al-Yasiri further emphasized the role of Syrians abroad in filling this gap:

“An important point in our discussion is the ability of Syrians abroad to advocate for those inside, and to support what they face and need — specifically by networking and building a support network that includes practitioners inside and outside Syria and with individuals or advocacy groups specialized in the legal and rights context for artists and cultural workers”.

Author: Nawar Alhusari

Nawar Alhusari is a Syrian visual artist, researcher, and lecturer. He holds an MFA in Graphics from Damascus University. His ongoing practice-based research explores the role of language, memory, and positionality as instruments of expression and representation under structural social and political discourses. His practices and teaching experiences experiment with artistic methods and political tensions as triggers for practice, production, and critique. He is currently a PhD candidate at Bauhaus University Weimar in Germany.