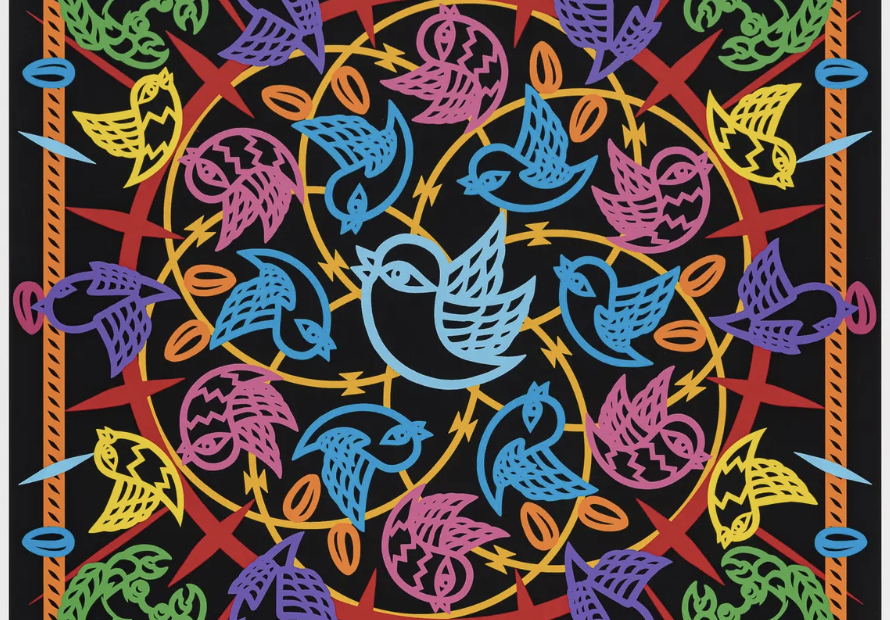

Ai Weiwei, Free Speech, 2023, image courtesy of Avant Arte: A tangle of barbed wire traps numerous symbols of free speech: the iconic Twitter bird, sunflower seeds (an Ai Weiwei shorthand symbol for the residents of China), and mud crabs (a meme icon in China symbolising the teams of censors that suppress free speech online).

“In the context of censorship in the West, there was a prevailing illusion that the West embodied greater freedom of speech and press, portraying itself as a society with minimal censorship. Yet, I believe that censorship persists wherever there is power. Unlike traditional authoritarian regimes that directly target individual speech, censorship in the West manifests itself more subtly within the framework of so-called democratic politics and the broader concept of so-called freedom of speech. Criticism and dissenting thoughts that diverge from the established values and corporate interests are often subjected to censorship to varying degrees.”

So says Ai Weiwei, an artist whose life has been shaped by artistic restriction. Ai Weiwei whose early life was spent in a North China labour camp because his poet father had not compromised his artistic vision. Who, as a result of his art, has spent months in a windowless room, his every action scrutinised by armed guards. Who now spends his days between different nations since he is exiled from his home country.

This artist who has felt the full force of artistic censorship and authoritarian brutality is now calling out Western states like the UK for the state of artistic freedom. Why?

The short answer is that Ai Weiwei has just been censored once again, only this time on British soil. In November 2023, the artist’s upcoming exhibition at the Lisson Gallery in London was unceremoniously dropped due to statements he had made on X (formerly Twitter) in relation to Israel’s invasion of Gaza. The offending tweet was a response to a follower who has asked for his take on the conflict. The tweet read: “The sense of guilt around the persecution of the Jewish people has been, at times, transferred to offset the Arab world.”

In a political environment still reeling from the attack by members of Hamas on October 7th, and the devastating retaliation by Israel that has followed, the gallery rapidly decided to indefinitely postpone the exhibition. In its statement, the Lisson Gallery argued that its exhibition space was “no place for debate that can be characterised as anti-Semitic or Islamophobic […] all efforts should be on ending the tragic suffering in Israeli and Palestinian territories, as well as in communities internationally”. In a later interview, Ai stated that the decision was made “to avoid further disputes and for my own well-being.” It is an oddly general statement that seems to miss the context or nuance with which Ai’s statement was made. The conflict between Israel and Hamas has caused significant cracks to appear in issues of freedom of expression in several nations, the UK being key among them. In a recent in-depth report on the mechanics of the defence of artistic freedom, IFA make the following statement:

“In November 2023, four UN Special Rapporteurs issued a statement of alarm about the reprisals against people who speak out on the conflict, identifying artists as being particularly targeted. The statement reads: “Calls for an end to the violence and attacks in Gaza, or for a humanitarian ceasefire, or criticism of Israeli government’s policies and actions, have in too many contexts been misleadingly equated with support for terrorism or antisemitism. This stifles free expression, including artistic expression, and creates an atmosphere of fear to participate in public life. […] In other contexts, we also see a rise in antisemitic speech as well as intolerance, for those who support or are perceived to support Israel, or who express mere sympathy for Israeli suffering in the aftermath of the 7 October attack. […] This leaves little space for moderate views.” (UN OHCHR, 2023).“

Speaking later about the matter, Ai Weiwei has stated: “If culture is a form of soft power, this represents a method of soft violence aimed at stifling voices. It’s not directed solely at me but at the broader culture of a society lacking a spiritual immune system. When a society cannot withstand diverse voices, it teeters on the brink of collapse.”

This is not an isolated incident. The same hesitance and sensitivity to public and political retaliation has been mirrored by institutions across the UK. The domino effect that has led to Ai Weiwei’s indefinite cancellation requires elucidation, and a great deal of attention. The nature of human rights is such that they are only truly visible in their absence; their necessity only becomes apparent when they are taken away. In the case of the right to freedom of expression, it often takes a sensationalist act of censorship in order to shed light on a much greater and entrenched problem. In their annual report on artistic freedom, the NGO Freemuse distinguishes between what they term “over-” and “under-the-radar” forms of censorship. Where over-the-radar incidents such as Ai Weiwei’s cancellation make the rounds across news outlets and show a sensationalist, yet localised, moment of restriction, these events are often markers in a much larger landscape of under-the-radar, covert forms of censorship.

When left unaccounted for, the chilling effect of smaller, more private forms of censorship leads to an artistic environment tempered by self-censorship, divestment, and decreased levels of political will and agency amongst artists. As the political temperature of the world rises to boiling point, the walls seem to be closing in on artists freedom in the UK.

At Arm’s Length

In Britain, arts are one of many sectors that are – supposedly – off limits to government interference. The British government is a major patron of the arts and funds many arts projects on a national and community-based scale. All funding is filtered through Arts Council England (ACE) via an “arms-length” policy. On paper, whilst ACE operates as a branch of the government, it does so – must do so – at a safe distance from the various goings on in the Houses of Parliament. However, despite the fact that the two bodies are at arms-length from one another, ACE-supported projects are still anecdotally recognised as government supported, validated, and oftentimes, projects funded by ACE fall under greater scrutiny as a result of public tax-funded patronage.

Just in the last year, if one were to look at British national television, one might assume that artistic freedom and political freedom of speech in the country is in vigorous good health. In 2023, British self-deprecating humour and satire was shown in full force through the television musical Prince Andrew: The Musical, a mocking comedy about the disgraced royal and alleged sex offender Prince Andrew, Duke of York, and again in Partygate, a satirical mockumentary centering on the illegal activities of ex-prime minister Boris Johnson and his cohort during the Covid lockdowns. In many other countries around the world, where lèse-majesté laws restrict anything bordering insult to a head of state, parody such as this would be unthinkable, heavily punished, and maybe even fatal to any artist who dared attempt something so brazen – let alone on a state-supported broadcaster during a primetime television spot.

This is something of a point of pride of the British cultural facade: a well funded, independent, progressive arts sector, in which individuals are welcome to produce politically complex and incendiary artworks. British satire and political commentary is funded like a badge of pride in the nation’s capital, and artists amateur and professional alike are invited to apply for government grants to fund their practice.

That is, on the surface at least. In 2024, cracks are beginning to show.

Since 2020, in the rupture of the pandemic, Europe has been swept up in a global trend of increasing levels of artistic censorship. Exacerbated by the rise of right-wing populism across the continent, and the near-mythical so-called “culture wars” and “cancel culture” that are being fought on mostly right-wing news outlets, arts censorship and silencing are on the rise. The escalation of violence in Gaza has had an exponential effect. This is particularly the case in nations often held up as bastions of democracy, freedom, and tolerance such as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

Herein lies the paradox: the UK prides itself on its political openness and artistic freedom, yet arts censorship is on the rise. What does this look like?

Arnolfini Gallery. Image by Martin Booth, via Bristol 24/7

https://www.bristol247.com/news-and-features/news/arnolfini-in-positive-talks-following-backlash-to-cancellation-of-palestinian-film-events/

Legally Obliged

In 2023, a major warning shot of tightening restrictions sounded when a major contemporary art gallery made the decision to drop a Palestinian film screening and poetry event. The Arnolfini is a popular modern art gallery in the heart of Bristol – a city often considered highly liberal and progressive that has recently been at the centre of the BLM and free protest movements.

The Bristol Palestinian Film Festival has been active since 2011. It’s a key event in a city recognised as a city of sanctuary for refugees and asylum seekers. However, last year in the wake of the escalated violence in Gaza, the Arnolfini gallery made the decision to drop its planned film and poetry event: a showing of the film Farha (2021) by Jordanian-Palestinian director Darin J. Sallam, set during the Nakba after the 1948 Palestine war, as well as a poetry reading by artivist Lowkey.

Whilst the individual events were instead held at different Bristol venues, the cancellation caused outrage across Bristol and has had ripple effects across the UK arts sector. When urged to explain why they had made the decision to cancel the urgently needed, and highly celebrated event, Arnolfini cited governmental pressure, stating that as an arts charity they were “legally obliged” to follow governmental guidance on remaining “apolitical”. In a statement, the publicly-funded gallery stated that they “could not be confident that the events would not stray into political activity”.

Poster for Farha (2021) directed by Darin J. Sallam. Image by TaleBox – IMDb (direct link to file), Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=72408815

However, in an open letter with more than 2,300 signatories, protestors queried this response from an organisation that has a history of platforming overtly political events and exhibitions, including events platforming refugee rights, the Black Lives Matter movement and a recent fundraiser campaign supporting Ukraine. The flimsy response and knee-jerk decision to drop a pre-planned, highly publicised event speaks of a greater level of fear in the UK arts industry, of a level of retaliation that is out-of-touch with the realities of the public to which these institutions serve.

In the aftermath, the Arnolfini has acknowledged the uncertainty the decision was made in, referencing a genuine concern for the safety of their staff in the wake of the Gaza conflict, as well as a lack of information from government advisors. The gallery has since apologised unreservedly for the decisions made, and released a statement expressing their commitment to rebuilding relationships that had been damaged by the cancellation. However, the incident has not been easily overlooked, with many high profile artists such as Brian Eno, Adham Faramawy, Tai Shani, as well as hundreds of local artists observing a boycott of the venue.

Terms and Conditions

To an outsider’s perspective, incidents like that of the Lisson and Arnolfini galleries may seem localised and isolated–the decisions of independent and fallible organisations negotiating their own biases and reputations. However, this February the mask worn by the British culture industry has slipped, and the topic of arts freedom in the UK was pushed into the attention of a public, already inundated with warning signs from the increasing levels of restriction abroad.

On January 25th, 2024, ACE – by far the UK’s largest and most depended-upon funding body – added an update on their website to their Relationship Framework policies–a cluster of policies that outline the relationship between the funding and the artists it funds. The new guidelines seemingly posed a warning to the culture sector: that the production of political work, and the expression of political opinions that “might be perceived as being in conflict with the purposes of public funding of culture”, run a reputational risk. The statement, since changed, suggested that any work that is “overtly political or activist” may risk their funding agreements:

“We define reputational risk as any activity or behaviour (for example, programming, events, statements (including about matters of current political debate), management decisions etc) that potentially breaches the terms and conditions of the funding agreement and/or is likely to result in negative or damaging reactions or coverage from the press, public, partners and/or stakeholders (eg sponsors and/or other funders) towards the organisation or the Arts Council.”

[These activities include those that] “might be deemed controversial, activity that might be considered to be overtly political or activist and goes beyond your company’s core purpose and partnerships with organisations that might be perceived as being in conflict with the purposes of public funding of culture.”

Again, the language here speaks of the under-the-radar, covert nature of censorship in Britain. The language used is steeped in the calling card of censorship: vaguery. The definition of what might be deemed “overtly political” or “activist” is not defined. As a result, the onus of decision making is left up to the individuals and institutions, whose livelihoods depend on their relationship with the ACE. Time and again, the role of jury is outsourced to “the public”, a hypothetical crowd ready to punish those who overstep their publicly-funded role as artists and entertainers. By forcing attention to the “purposes of public funding of culture”, artists are cajoled into scrutinising their own actions against an imagined public consciousness.

When first reported on by Arts Professional on X in February, the backlash and uproar that followed was immediate. Many took the guidance to represent an outright warning to artists and institutions: perform politics at your own risk, your funding agreements are yours to lose. Whilst ACE were quick to counter claims of governmental censorship or silencing, claiming that they were by no means steadfast rules that affected artists’ funding eligibility but rather advice to artists to consider their own reputational risks, many were unconvinced. The chilling effect that a statement like this might have, amid a heightened political climate and in light of the two incidents already mentioned, was a clarion call that has resounded around the UK cultural sectors. In 2024, the role of Arts Council England is up for review–a fact that may play a significant role in this year’s leadership election. If this incident is a warning sign of things to come, the UK may see the arm’s-length distance between government and the arts tightening.

Kneecapped

For all the claims of the British Conservative government’s supposed “hands off” approach to the arts, one major mark against them is the fact that they are currently involved in a legal action against them on accusations of injust censorship.

In early 2024, the British government sponsored the Music Export Growth scheme, helmed by the UK secretary of state for business and trade, Kemi Badenoch. The fund totals £1.6 billion and is devoted to supporting homegrown musicians and artists, to expand their careers outside of the British Isles. It’s an important opportunity for up-and-coming musicians, which has in the past launched the international profile of many Mercury Prize winning artists and groups. An opportunity that, if gatekept, would be a devastating indicator of the state of affairs in Britain.

Tweet via Kneecap, accessible : https://x.com/KNEECAPCEOL/status/1755980413258895456

That however, is exactly what happened early this year, when an Irish-language rap trio, Kneecap, had their prize grant rescinded after intervention by the British government. Kneecap – who consist of artists Mo Chara, Móglaí Bap and DJ Próvaí– are steadily building momentum and hype for their biting satirical and hard-hitting grime, which is delivered in a mix of English and Irish. They are rising stars that wear their Republicanist politics on their sleeves, promoting Irish language and speaking out against occupation (they were one of a slew of artists that sacrificed a coveted slot at SXSW this year in protest of the festival’s donor ties to Israeli arms deals). Their lyrics often make a mockery of post-Brexit Britain and Ireland, lampooning specific politicians and policies, not least in their recent single Get Your Brits Out.

It’s this last point that has got the trio in the Conservative Party’s bad books. When choosing Kneecap for the prized grant, the governmental jury must not have had a read through of the group’s lyric book. Either that, or forgotten to write a rule stating that music that expressed criticism of the UK were ineligible for funding. A spokesperson for Badenoch stated in February: “We fully support freedom of speech, but it’s hardly surprising that we don’t want to hand out UK taxpayers’ money to people that oppose the United Kingdom itself.” With that, the £15,000 grant awarded to Kneecap was blocked, and the group removed from the support scheme.

It was a decision as short-sighted as it was arbitrary. In a stunning act of comeuppance, the government department behind the scheme, as well as Badenoch herself, are being taken to court by Kneecap via a Belfast-based human rights legal group Phoenix, an act that has easily already rewarded them a reputation to rival the potential gains of a £15,000 grant, and has had the effect of shedding light on the fragility of a ruling party at crisis point.

A Censored Arts Industry?

It is easy to see these incidents in isolation; separate instances made in the heat of a tumultuous political period. However, research by freedom of expression monitors such as Freemuse, IFA, and the Council of Europe urges us to pay attention. Episodes such as those listed above are often waypoints on a much larger landscape which, if we are to map it, must be thoroughly scrutinised. Institutions are recoiling out of fear of the backlash or retaliation at what shareholders and donors might have to say about their actions – with blame outsourced to the general public “public opinion”.

What each of these incidents share is a lack of nuance, a moment of knee jerk recoil in an overheated political climate, with a seeming refusal or unwillingness to consider context, expression, interplay or subtext. As Ai Weiwei states, censorship in the “West” manifests much more subtly than in outright authoritarian regimes, and in order to properly scrutinise arts censorship as such, one must be willing to connect the dots that make up power structures in the cultural industry.

It remains to be seen whether these incidents will escalate, and whether the UK will have to contend with a problem of artistic freedom. What these episodes have revealed however is that the state of freedom of expression in the nation–a point of pride in the British international image–is fallible. Going into the latter half of 2024, parties across the political spectrum will be certain to try to brush these incidents under the carpet; currently the role of the Arts Council is under review, and July will see a major leadership election. Whilst the topic of global conflicts will undoubtedly play a central role in the election discourse to come, the past 14 years of Conservative austerity has left the UK cultural industry in hobbling precarity, with arts education and platforming being slashed across the nation. Both major political parties are poised to inherit a cultural sector that has been badly burned, and incidents like those explored above only serve to deepen the tension.

Author: Ed Holland

Ed Holland is a cultural researcher and writer with a deep interest in how societies harness the signs, symbols, and affordances of art and artists, and use them as tools of politics, representation, or self-definition. Ed’s research is centred around freedom of expression rights and arts freedom, exploring how arts sectors around the world variously fall under the coercion of – and actively resist – authoritarian control and pressure. As a writer he is interested in “silent” art, whether in the form of art that is censored, outsider artists working outside the categories of the mainstream, or overlooked icons of the counterculture.

Linkedin: linkedin.com/in/ed-jb-holland/

Medium: medium.com/@ed.

References

Artists for Palestine UK. 2023. Olivia Colman among 1000+ artists accusing art institutions of censorship on Palestine. <https://artistsforpalestine.org.uk/2023/11/30/olivia-colman-among-1000-artists-accusing-art-institutions-of-censorship-on-palestine/>

Artists for Palestine UK. 2023. Leading artists disengage from British venue that censored Palestine.

The Arts Newspaper. 2023. Ai Weiwei criticises ‘fragile’ state of Western democracy following Sky News interview.

The Arts Newspaper. 2023. Lisson Gallery puts Ai Weiwei London show on hold over Israel-Hamas war tweet.

Arts Professional. 2024. Badenoch blocks grant for NI rap trio over political views. <https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/news/badenoch-blocks-grant-ni-rap-trio-over-political-views>

Council of Europe. 2023. Free to Create: Artistic Freedom in Europe. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Freemuse. 2020. Security, Creativity, Tolerance and their Co-Existence: The New European Agenda on Freedom of Artistic Expression.

Freemuse. 2022. State of Artistic Freedom 2022. Copenhagen: Freemuse.

Hyperallergic. 2023. Ai Weiwei Speaks Out on Cancellation of His London Exhibition. <https://hyperallergic.com/856763/ai-weiwei-speaks-out-on-cancellation-of-his-london-exhibition-lisson-gallery/>

Reitov, O., & Whyatt, S. 2024. The Fragile Triangle of Artistic Freedom: A Study of the Documentation and Monitoring of Artistic Freedom in the Global Landscape. IFA.