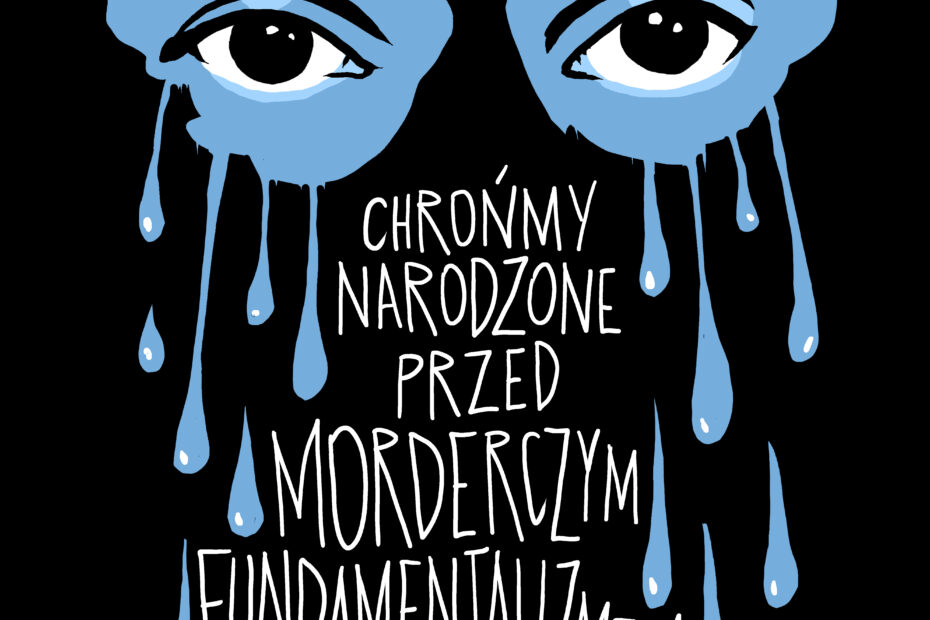

Marta Frej – Chrońmy narodzone przed morderczym fundamentalizmen (Let us protect the living from murderous fundamentalism)

In November 2023, Polish majority voters demonstrated support for a coalition of liberal and centrist parties that campaigned on bringing Poland back into alignment with its EU allies on key issues and reversing democratic backsliding. Since taking office in December, the coalition’s newly elected Prime Minister, Donald Tusk, has faced the difficult task of reforming many of the problematic laws and policies put in place by the outgoing administration, Law and Justice (PiS), including measures taken to limit judicial independence and media plurality. In addition to reforming key democratic institutions, Tusk’s administration will also have the opportunity to restore protections for fundamental rights and freedoms in Poland that were undermined by PiS, notably the right to freedom of artistic expression.

In September 2022, my colleagues and I at the Artistic Freedom Initiative (AFI) published Cultural Control: Censorship and Suppression of the arts in Poland. Our report covered challenges to free artistic expression in the country, and exposed how the PiS administration used law and cultural policies to suppress their opponents and critics, including a large number of artists. In the course of our research, we found that the key strategy PiS employed to effectuate this aim was to use an existing blasphemy law to intimidate or punish artists.

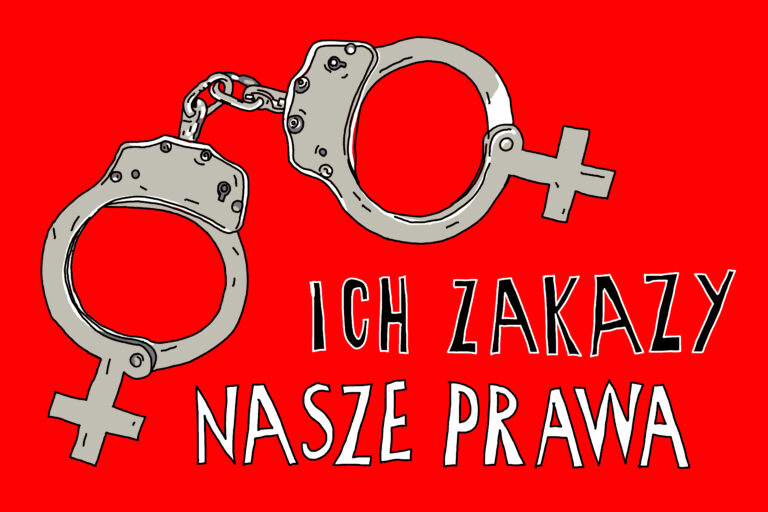

Marta Frej – Ich zakazy nasze prawa (Their bans our rights scaled)

International human rights bodies generally reject the use of blasphemy laws as illegitimate impediments on free expression. In the 2012 Rabat Plan of Action on issues related to freedom of expression, the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) concluded that in most cases, blasphemy laws are dangerous because they undermine democracy by affording preferential protections to individuals or institutions. They stated: “[A]t the national level, blasphemy laws are counter-productive, since they may result in the de facto censure of all inter-religious/belief and intra-religious/belief dialogue, debate, and also criticism, most of which could be constructive, healthy, and needed.” [1]

Poland’s blasphemy law is enshrined under Article 196 of the Polish penal code, which states that “[a]nyone found guilty of offending religious feelings through public calumny through an object or place of worship is liable to a fine, restriction of liberty, or a maximum two-year prison sentence.” [2] While blasphemy laws are problematic in general for the reasons listed above, Poland’s Article 196 is particularly concerning because its vague language fails to prescribe the legal threshold for “offending religious feelings.” Speaking on the shortcomings of the law, a member of the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission remarked, “The religious feelings of the different members of one specific Church or confession are very diverse. The question is: whose level of religious sensibility should we treat as the average level—the sensibility of a group of fundamentalist or tolerant members?” [3] Beyond the issue of vagueness, the law is also incompatible with international standards on freedom of expression because the criminal punishment of a two year prison sentence is disproportionate to the severity of the crime of “offending” someone in the course of self-expression.

It is easy to imagine how an artist, fearing criminal punishment, would self-censor to avoid negative scrutiny from a religious fanatic, which indeed appears to be a growing phenomenon in Poland. During PiS’s administration, the number of arrests and charges under Article 196 increased significantly; In 2016, there were only ten criminal indictments alleging a violation of Article 196, but in 2020 that number rose to 29 indictments. [4]

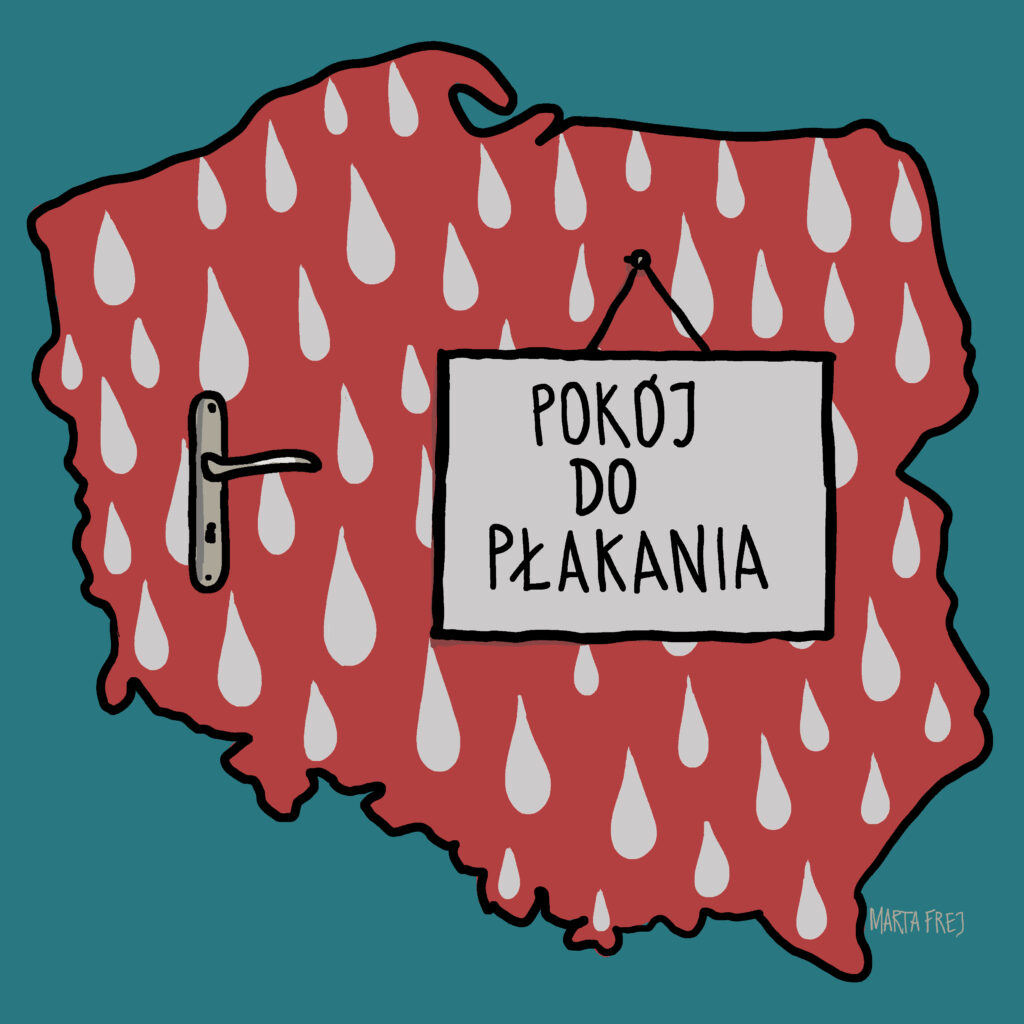

Marta Frej – Polityka episkopat (Episcopal policy)

In Poland, the vast majority of charges under Article 196 are made by Catholics, the dominant religious group in the country, who claim that their religious feelings were offended by artists whose works challenge or make reference to Catholicism in a critical way. In practice, the law weakens democratic values by sending a message to the public that the Catholic Church will receive state special protection from critical narratives. While freedom of religion is of equal importance to freedom of expression in a democratic society, and therefore deserving of equal protections, the right to freedom of religion can be sufficiently protected by laws preventing incitement to violence, discrimination, or hate, as is necessary to maintain peace in a democratic society. In contrast, protecting individuals’ “religious feelings” through blasphemy laws stifles free expression in order to insulate religions and religious institutions from criticism, which is not a legitimate aim of the law.

The law also weakens democratic values because it has a ‘chilling effect’ [5] on free speech; it incites fear in artists and, consequently, causes them to self-censor their ideas. In practice, a majority of the Article 196 cases are ultimately dismissed or acquitted by the prosecutor’s office. However, the legal process itself, as well as the negative consequences associated with the allegations, succeed in deterring artists from freely expressing themselves.

In Cultural Control we spoke with the Polish visual artist, Marta Frej, about her experience with this law and the effect it has on artists’ free speech. In 2021, Ordo Iuris, a conservative legal group brought allegations against Frej for one of her artworks. The work in question showed a figure like the Virgin Mary wearing a covid-protective face mask with a red lightning bolt on it, a symbol of the women’s reproductive rights movement in Poland. Frej was questioned by the prosecutor’s office in June 2021 regarding her artwork and though the charges were ultimately dismissed, the allegation itself came with negative consequences that affected Frej’s professional and personal life. Prior to the dismissal of the allegation, Ordo Iuris launched a social media campaign denouncing Frej’s work. Their campaign was further sensationalized by conservative media outlets that called Frej’s work “scandalous” and “insulting.” At the time, Frej was about to publish Dromedaries, a book featuring one of her collections, and she had a deal with the national bookseller, Empik, to release it. However, in response to the negative media coverage, Empik expressed hesitancy about carrying the book. Though the bookseller ultimately authorized a limited release of the book, but canceled the larger roll-out they had initially discussed, causing Frej to lose out on significant potential earnings. Further, having to pay legal defense fees for charges that are ultimately dismissed is a significant financial set-back for artists like Frej.

Marta Frej – Pokoj do plakania (Weaping room)

Wary of the legal, financial, professional, and social consequences that come with allegations under the blasphemy law, Frej said that she now routinely consults her lawyer before releasing new work in Poland. She shared, “The reality is that I can’t actually ascertain the degree to which I engage with self-censorship now — I don’t know how many ideas I’ve reconsidered because I was tired and fed up and didn’t want to worry about someone showing up to my house to drag me to the prosecutor’s office.”

Frej’s remarks pinpoint what makes Poland’s blasphemy law insidious; even though most allegations result in acquittals, the negative side-effects of the cases – including steep legal defense fees, reputational damage, and professional losses – cause many Polish artists to self-censor to avoid them. Such self-censorship is the direct result of the chilling effect that the blasphemy law has on free artistic expression in Poland, and demonstrates why the draconian law should be repealed.

Though Poland’s blasphemy law is the most infamous in Europe, many European countries have similar laws. According to a 2019 PEW research study, more than 14 European countries still have blasphemy laws, though most are relics of a distant past and have fallen into near-total disuse. [6] Because their disuse has rendered the laws essentially moot, many states haven’t taken the initiative to start the lengthy process of revising or repealing them. However, PiS’s revival of the blasphemy law as a means to deter artists and other opponents from exercising their right to free expression is a compelling reason for European states to take such initiative. As long as such laws continue to exist, even when inactive, they undermine democratic values and risk limiting the full range of expression possible in society.

In solidarity with Polish artists and creatives, AFI urges the Donald Tusk administration to take action to repeal Article 196 of the Polish penal code. We also encourage European states to fortify protections for freedom of expression by revising or repealing outdated blasphemy law in their countries.

Author: Johanna Bankston, Senior Officer of Human Rights Research & Policy at Artistic Freedom Initiative (AFI)

Johanna Bankston is AFI’s Senior Officer of Human Rights Research and Policy, where she leads the organization’s research and advocacy program, including serving as a lead author and editor on all of AFI’s research reports on artistic freedom around the world. As a researcher, Ms. Bankston’s topics of strongest interest are in free expression, migration governance, and human rights.

Notes

[1]“Rabat Plan of Action – Istanbul Process 16/18.” 2020a. Istanbul Process 16/18. September 8, 2020.

[2] Polish Penal Code, Article 196

[3] Freedomhouse (2010) Policing Belief: The impact of blasphemy laws on human rights – Poland, Freedomhouse, Available at: https://www.freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/PolicingBelief_Poland.pdf

[4] Sethi, S. et. al. (2022) Cultural Control: Censorship and Suppression of the arts in Poland, Artistic Freedom Initiative, Accessible at: https://artisticfreedominitiative.org/projects/artistic-freedom-monitor/poland/

[5] Pech, L. (2021) The Concept of the Chilling Effect: Its untapped potential to better protect democracy, the rule of law, and fundamental rights in the EU, Open Society Foundations. March Accessible at: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/the-concept-of-chilling-effect

[6] Villa, V. (2022) Four-in-ten countries and territories worldwide had blasphemy laws in 2019, PEW, Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/01/25/four-in-ten-countries-and-territories-worldwide-had-blasphemy-laws-in-2019-2/