By exploring 4 gems of recent Palestinian cinema, journalist Sarina Soleymani explores how the particularities of film and storytelling are a crucial means of overcoming divisive rhetoric and false dichotomies in world politics. Sarina shows that in regions undergoing harrowing conflict and politicisation, even simple depictions of daily life can become an act of defiance.

The essence of art can be said to be the encapsulation of a wide range of emotions whether it be joy, pain, love, or anger. This encapsulation serves as a catalyst for conversations that in turn can lead to de-mystification and promote open-mindedness. As it concerns the capacity to cause political change, art’s ripple effects are needed to cultivate solidarity and foster empathy which explains why it can be used as a form of resistance. In highly politicized and deeply polarized contexts, art can be used to resist stereotypes, occupation, and cultural erasure by reinstating an identity and experiences. The creation and diffusion of Palestinian artwork accomplishes exactly that.

In his book “The Origins of Palestinian Art”, Bashir Makhoul notes that the politicized context of Palestine makes it absurd to try to distinguish ‘political art’ from non-politicized works. In Palestine a simple cactus can be read as a nationalist message, and the use of certain colors risks placing artists in jail. The latter is a reference to the banning of the gathering of the colors of the Palestinian flag from 1967-1993 and to leading artists such as Fathi Ghaben (1947-2024) being put in prison for the ‘crime’ of painting using the green, black, white and red of Palestine. Such inherent politicization is forced into every aspect of Palestinian life, thus a ‘simple’ focus on individual lives can become in itself a form of resistance and solidarity.

The vast ocean of artistic resilience in Palestine extends from the traditional Dabke to the Arab Futurism of Sansour. Nonetheless, in order to limit our scope, this article will be oriented primarily on what is called the ‘seventh art’; the combination of visuals, sound, dialogue, and emotion which glimpse into the realities of Palestinian life and humanize the population to global audiences: cinema.

“When you live under occupation, you have different forms of resistance than those in normal regimes and one of the ways is culture”.

These are the words of Rawan Odeh, the co-founder of the association “Cine-Palestine” in Paris and Marseille, who kindly offered her insight and experiences in organizing cinema festivals and their role in creating crucial conversations in an interview taken place on the 8th of November, 2023. According to Odeh, it is rare to find Palestinian films in France. Having an association dedicated to shedding light on the Palestinian experience creates space for an alternative narrative. Cine-Palestine’s work allows audiences to speak to film directors, allowing productive exchanges with those unfamiliar with the extent of political struggles in daily Palestinian life and those who have lived through it first-hand. Through a compilation of this enriching interview alongside an analysis of some beautiful Palestinian films, this article hopes to convince the reader to consult these gems which lie in the world of Palestinian cinema.

“When I left, I realized that people do not know anything about my country, all the time it is stereotypes,” Odeh described. Here, she is referring to how language is weaponized by the media to paint civilians as “barbaric” or “terrorists” and diminish the occupation to a “conflict”. Through gripping storylines and compelling characters, cinema immerses viewers in the lived experiences of Palestinians, challenging preconceived notions, and offering a raw, unfiltered portrayal of their resilience in the face of oppression.

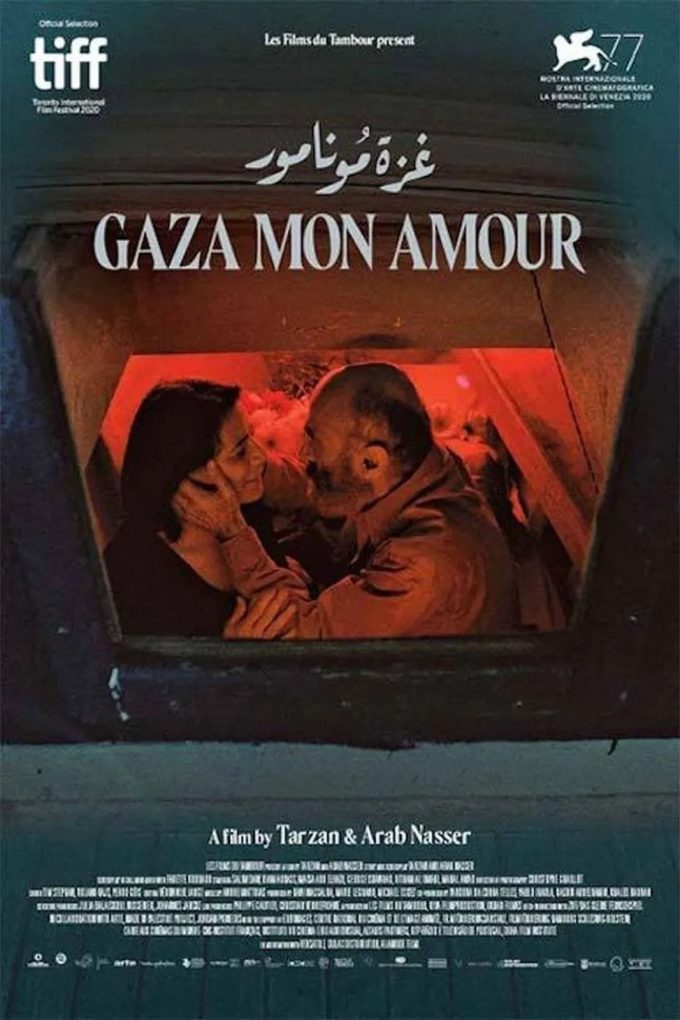

Poster for Gaza Mon Amour (2020) directed by Arab Nasser & Tarzan Nasser. Wikimedia, Fair use, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/e/e7/Gaza_mon_amour.jpghttps://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=72408815

One such film that manages to circumvent the often dehumanizing effect of global media narratives is Gaza, Mon Amour (2020), the impressive work of the Gazan brothers, Tarzan and Arab Nasser. Nominated for three awards in the Academy of César and received several other awards, the film follows a simple love story told through comic undertones of two middle-aged individuals in Gaza. Based on a true story, the couple’s romance blossoms after the main protagonist is arrested by Hamas for finding and attempting to sell a statue of Apollo. The beauty of this film is that it shows a real, simple, and authentic story; In doing so it illustrates the obvious: Palestinians are also people, they also experience love even in politicized contexts. It exemplifies a concept expressed by Odeh: films portray universal feelings, allowing one to humanize the Other, through shared experiences like love, birthdays, and the experiences of women. As she expressed, “That is what makes us human, we have so much in common even if we experience them from far away.”

I had the pleasure of watching this phenomenal film in a screening where one of the directors (Arab Nasser) was present allowing for an exchange with him following the film. He spotlighted the significance of the film’s subtleties, such as the choice of two middle-aged lovers as opposed to the common romantic trope of focusing on young protagonists. This small detail was to capture the tragic reality that causes the young people in Gaza to flee, to look for a life elsewhere in a safe environment that allows them the human rights they deserve, alongside opportunities that should be available to any person. He explained that this film used this simple story to highlight all the layers of oppression and injustice in Gaza starting from the internal struggles, whether political or economic, to the harsh laws of Hamas to finally, and only at the end, the Israeli occupation. This enriching film allows one to understand the true dynamics of living in Gaza, the political dust which surrounds the place and how constant injustice hinders a “normal” life. Simultaneously, it spotlights how people manage to find laughter, love, and joy within harsh times. The film allows non-Palestinians to witness a lifestyle that they would otherwise be unfamiliar with. It shows us elements that one cannot find in research, through articles or in the media and such humanization causes people to care and come together for their cause.

It Must Be Heaven (2019) directed by Elia Suleiman. IMDB, Fair use, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt8359842/

Palestinian cinema allows filmmakers the option to choose their own story instead of needing to operate within the limits of any imposed narrative from any party. Such an idea is found in the work of Palestinian director Elia Suleiman, It Must Be Heaven (2019): is a captivating, satirical film that received the Jury Special Mention award at the 2019 Cannes Festival. In this piece, Suleiman plays himself as he travels from Nazareth to Paris and on to New York, silently observing absurd scenes taking place, which in my eyes shows a certain irony in the heavenly-painted West. Although not a biographic piece, the director stressed that every sentence included in his film was based on phrases he actually heard. Moreover, he highlights his idea of a “Palestinisation of the world” in which the violence of his home is reflected everywhere, on larger or smaller scales, and his trauma follows him. In other words, he illustrates how Palestine is a global issue, a global struggle against violence and discrimination, which can be manifested even in the supposed “heaven” of the West. The choice of a silent film is especially interesting as it begs us to ask why he is muted throughout the film, whether it was a conscious choice or his voice taken from him, forcing him to be silent. His comedic depiction of the authorities belittles their power but also comments on the lack of true freedom in the West. As an immigrant from the Middle East, I truly felt the depicted difficulties present in these so-called “free” countries (which are nonetheless more free than our country of origin) where their hypocrisy and de-politicization of political experiences—that of injustice, power imbalances, discrimination—triggers a frustration which can only truly be expressed comically.

“It must be heaven” because it was told to us that this is heaven. “It must be heaven” because we must have gone through hell to wish to be here. “It must be heaven”, but it is not heaven—and if it is, then maybe only in the very broad sense of the term—and our countries were not hell—at least not in the strict sense of the term. The director commented on the mythologisation of Palestinians through a scene in which a New York taxi driver gives him a free ride after finding out his nationality, claiming that he was the first Palestinian he had ever seen, as though he was a mythical creature. Suleiman further spotlights the discrimination faced by Palestinians in the diaspora through a chilling yet nonetheless artistic–and in part comedic–scene where the police chase after a Palestinian woman in an angel costume for wearing the flag of her country.

The memory of Palestine is everywhere. The theme of being constantly on the move with persistent shots in which characters or vehicles are moving comments on the freedom of movement that is not available to those living in occupied Palestine, whether that be in Gaza or in the West Bank. The theme of the Western perception of the Middle East is further depicted through a character expressing that a film about peace in the Middle East is “funny already” pretending as though the Middle East was made inherently unstable to the point that peace is only a far-fetched idea. Ignorance was depicted through other visual symbolism in which his character merely witnesses but never intervenes, a comment I found to be reminiscent of Western individualism where one can observe but continue with their day, ignoring the chaos and bloodshed in Palestine. But the pinnacle of the film occurs in a scene in Paris, as a French producer turns down the protagonist’s film idea as he found it to not be “Palestinian enough.” It is an ironic criticism of how people try to stick a narrative onto Palestinian stories, how some people are forced to be outwardly political and that their life experiences are not seen as “enough”. Elia Suleiman reclaims his story and identity through this film, bringing out conversations that may not seem overtly political, yet are nonetheless crucial to understanding these realities on the individual level.

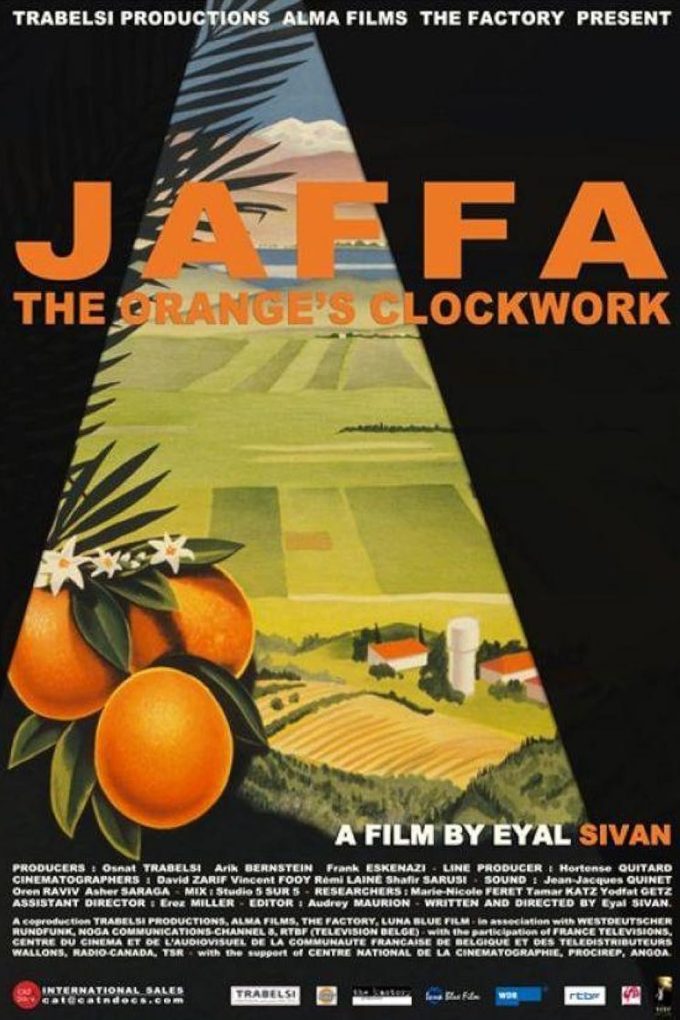

Poster for Jaffa, the Orange’s Clockwork (2009) directed by Eyal Sivan. IMDb, Fair use, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1720949/mediaviewer/rm2895971840/?ref_=tt_ov_ihttps://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=72408815

This year Cine-Palestine celebrates its 10-year anniversary by producing a festival on “archives”. As Odeh urges, archives are powerful: they do not merely teach a history or pass down an experience, but they prove it through the camera. She exemplifies this with the documentary: Jaffa, The Orange’s Clockwork (2009) by the Israeli director, Eyal Sivan. Born in Haifa in 1964, this fascinating filmmaker works on unraveling narratives through archives and individual experiences. His enriching work proves that it is possible to see through enforced polarization and focus on lived realities which were documented thanks to the camera. In this film one finds the use of oranges as a propaganda tool by the Israeli government, who claimed that there had been no oranges in the region before their arrival, only desert. Such a narrative played on an orientalist picture of the Arab world as an empty land, undeveloped territory which is characterized by the desert. Eyal Sivan shows through archival footage how the oranges did exist and were harvested by Palestinians. Such a statement of bare historical fact resists the erasure of Palestinian identity by the Israeli state propaganda. He further portrayed that peace existed in the community despite ethnicity or religion, alluding to how people are not the problem but rather state propaganda and state violence. The latter being the elements which led to forced expulsion and occupation of Palestinians creating such a rupture. His brilliant documentary highlights a core injustice when the name of this Palestinian city, Jaffa, becomes the name of an Israeli orange brand following the Nakba.

This leads us to discuss a key point in Palestinian history: the Nakba or “the catastrophe,” in Arabic. Integral to understanding the Palestinian struggle, the Nakba brings us back to 1948, following the end of the British Mandate, when Zionist troops expelled over 700,000 Palestinians from their homes whilst establishing the state of Israel. The popular film, Farha (2021), by the Palestinian-Jordanian director Darin J Sallam portrays an emotional account of the nakba using a real story of a young girl named Farha whose life was dramatically affected by these forced expulsions. We witness this girl who was just about to experience her dream life after moving to the city and finally being able to have the education she wishes, instead have her world turned upside down in this catastrophe. Her courageous choice to stay in her village despite the danger, separates her from her best friend. To ensure her safety, her father tries to keep her safe in a shelter where she witnesses the traumatizing horrors of expulsion. Losing her father, her best friend and her dreams, Farha is instead forced to flee into nothingness, with no direction, in order to—hopefully—find any semblance of safety.

Poster for Farha (2021) directed by Darin J. Sallam. Wikimedia, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=72408815

As Odeh revealed in his interview, their film festivals extend beyond the mere projection of the film, the full experience of their festivals is completed by the conversations. When people watch these stories, they even feel propelled by initial feelings of self-satisfaction as the mere act of watching Palestinian films can be viewed as a form of activism. As such, these stories prompt individuals to explore their curiosity, expand the discourse around the subject which not only educates viewers on the Palestinian experience but also—crucially—begs them to care. This specificity of film, the ability to connect to spectators, is precisely what makes it dangerous for those in power. For this reason, freedom of expression is not always guaranteed for such kinds of cinema, an industry that often faces intense state scrutiny and different kinds of censorship. In the case of Cine-Palestine, censorship escalated following the attacks of October 7. Social media platforms such as Facebook censored the advertisements of their events and did not allow them to either publish or reach the expected amount of audience.

Furthermore, Odeh tells us, the region of Provence-Alpes-Côte-D’Azur (PACA) in the south of France had blocked their funding. This meant that their association no longer had the means to continue showcasing films as they used to. In this instance the loss of funding acted as another form of censorship; the PACA region further falsely accused their association of supporting terrorism and antisemitism, an unfounded claim that tried to frame the diffusion of culture as a hateful act to dissuade audiences from interacting with Palestinian media. The false dichotomy of supporting Palestinian culture or rights being equated to the support of extreme violence and terrorism against the Jewish population is incredibly dangerous as it hinders dialogue. In my eyes, fighting for Palestinian rights through their culture goes hand in hand with ensuring the safety of the Jewish population and preserving their culture and religion: solidarity is a universal value. A people exposing the violence of their occupation by a state and military entity should not be equated to racism towards other people, the two are extremely distinct, and the false dichotomy paints both sides in a bad light whilst unfairly instrumentalizing the suffering of the Jewish people in the process. It is this false dichotomy that blinds people in such polarized situations and leads to fear of dialogue and tunnel vision.

Odeh expressed that these tensions make them “afraid of doing anything”, a context where even raising the Palestinian flag was under legal scrutiny. Cine-Palestine has previously experienced hateful acts not only towards their association but even Palestinian actors participating in their events. For instance, Mohammed Backrie, who played a role in Jenin, Jenin (2003) was attacked in front of a cinema theatre. In these instances, Odeh communicated that they had to constantly remind people that their work is about art and culture, and that Palestinians have a right to be artists and a right to culture. The right to participate in cultural life and the right to protection of the moral and material interests of artistic production are indeed international human rights for all human beings as stipulated under Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Restricting Palestinians from their artistic freedom is a violation of our collective responsibility to protect human rights. Undue censorship of content should always be rejected as it can always lead to a ripple effect to oppress other marginalized groups in the future. And, although it may seem small or insignificant, merely watching and disseminating these kinds of films, conversing and most importantly, listening, is in itself a resistance towards the undemocratic practice of censorship.

Currently, conversations surrounding the situation in Palestine privilege political actors, whether that be Hamas, or Benjamin Netanyahu and the IDF. These conversations have progressively shifted from human lives to statistics, or political and military strategies. I believe that we must take a step back. Before all, when we talk about Palestine, we are talking about humans, their lives and their rights. For this reason, it is crucial to first focus on individuals, their cultures, their stories and experiences and ground ourselves before viewing them as mere numbers. Our conversations should not be centered around a dichotomous polarization but try to listen to the affected souls. Once we begin to empathize with the lived experiences of real persons in these contexts, once we view a people as human, it becomes more difficult to process them getting bombed, losing their loved ones, or lying under the rubble. Emotional connection to a cause is the ingredient lacking in current media discourse and cinema is where it can be found. These films can remind us that before anything, an individual’s right to life and human dignity should be protected at all costs—especially before any political will or affiliation.

Author: Sarina Soleymani

Sarina is an undergraduate student at Sciences Po Paris, campus of Menton where she studies political humanities specializing in the Middle East and Mediterranean region. She is originally from Tehran yet she moved abroad from a young age to Beijing and later Paris. Despite this, she kept a strong link to her culture notably through art and cinema. Her fields of interest include journalism and the intersection of art and politics.

References

“Darin J. Sallam.” Palestine Filmer C’est Exister,

https://palestine-fce.ch/annuaire/darin-j-sallam/. Accessed 5 February 2024.

“Elia Suleiman on It Must Be Heaven | Sight and Sound.” BFI, 15 June 2021, https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/interviews/elia-suleiman-it-must-be-heaven-palestineparis-global-violence. Accessed 5 February 2024.

“Elia Suleiman on It Must Be Heaven | Sight and Sound.” BFI, 15 June 2021, https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/interviews/elia-suleiman-it-must-be-heaven-palestineparis-global-violence. Accessed 5 February 2024.

Haddad, Mohammed. “Nakba Day: What happened in Palestine in 1948? | Israel War on Gaza News.” Al Jazeera, 15 May 2022,

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/5/15/nakba-mapping-palestinian-villages-destroyed-by-israel-in-1948. Accessed 6 February 2024.

“International standards | OHCHR.” ohchr,

https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-cultural-rights/international-standards. Accessed 7 February 2024.

Massalha, Rani. “GAZA MON AMOUR – Film.” European Film Awards,

https://europeanfilmawards.eu/en_EN/film/gaza-mon-amour.19543. Accessed 4 February 2024.

Mucem. “Jaffa, the Orange’s Clockwork.” 9 November 2017,

https://www.mucem.org/en/jaffa-oranges-clockwork. Accessed 5 February 2024.

“Palestinian film Gaza Mon Amour nominated for 3 César awards – Screens – Arts & Culture.” Ahram Online, 19 January 2022,

https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/5/32/456611/Arts–Culture/Film/Palestinian-film-Gaza-Mon-Amour-nominated-for–C;s.aspx. Accessed 4 February 2024.

Piccino, Cristina. “Eyal Sivan: ‘If Israel is a model of democracy for the West, that scares me.’” Il manifesto global, 9 November 2023, https://global.ilmanifesto.it/eyal-sivan-if-israel-is-a-model-of-democracy-for-the-west-that-scares-me/. Accessed 5 February 2024.

“Seventy+ Years of Suffocation.” Amnesty International, https://nakba.amnesty.org/en/about/. Accessed 6 February 2024.

Sodha, Sonia. “Meet the modern-day censors, wielding their purse-strings over artists and their work | Sonia Sodha.” The Guardian, 18 February 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/feb/18/censorship-arts-council-england-funding. Accessed 2 April 2024.