Artwork: Sylvie Blum

Censored By: Instagram. Source: Don’t Delete Art Gallery

One of the most prevailing myths in our society is the myth of the starving artist: the artist whose destined success is intertwined with their pain. To young aspiring artists, this narrative can be deeply attractive; the notion that true art is borne from suffering, poverty and starvation is often presented as romantic and worthy. An artists’ work is gilded by their hardships, serving as not just an expression, but a totem.

This concept, that to suffer is to be worthy, and that even to find success in death is achievement, has fed more than one art-loving generation’s vision of what “good” art is and where it comes from. And there is a truth buried in all this romance, that speaks to how much we value art as a testament to the eternal and indestructible human need for expression. If one can create under even the worst of circumstances, then that work means infinitely more to us. As such, with art censorship notably on the rise around the world, instances of art censorship and oppression of artists have taken center stage as a vivid example of the ills of nationalism and its risk to freedom of expression. The jailing, execution, and silencing of artists in political regimes have gathered us all in a societal condemnation of such actions, and increased our appreciation for the struggle of these artists. But the value we have placed on the image of the starving artist, the telling of their story of woe and pain, has left some of the most insidious ways an artist is hindered, oppressed, and silenced just out of frame.

Artwork: Spencer Tunick

Title: Bodø Bodyscape 11 (Bodo Biennale, Norway) 2018

Censored By: Instagram. Source: Don’t Delete Art Gallery

A few weeks ago, Ai Weiwei, who has for years been a celebrated example of the bravery and resilience of the suffering artist, said that he believed the censorship in the west is “sometimes even worse” than Mao’s China. Telling The Art Newspaper in an interview about his comments, Weiwei expanded, saying “Unlike traditional authoritarian regimes that directly target individual speech, censorship in the West manifests itself more subtly within the framework of so-called democratic politics and the broader concept of so-called freedom of speech…That’s why I think Western censorship operates in a more concealed, solid and enduring manner. This poses a greater threat as people are lulled into believing in the absence of censorship in the West.” These comments from such a renowned and famously oppressed artist sent an undeniable chill of recognition down the spine of the western art world, especially as escalating and increasingly divisive events rock the structures and institutions many have taken for granted.

The ways in which the status quo has ruptured recently have been made visible in dramatic protests staged at major art institutions, fiery discourse on social media, and increasing cancel culture. Artists and activists within art communities across the western world have recently gathered and staged massive interventions at major institutions and events, expressing vociferous distrust that has been brought to a boiling point. Usually hindered by risk from speaking out — and, yet, at no less risk, now, for doing so— artists have gathered force together to call out museums for what they see as biased influences and behavior. In Germany, where tensions are particularly high over strict anti-semitism laws which have resulted in previous very public accusations of censorship, such as at the Dokumenta fair in 2022, Pro-Palestine protestors in February interrupted a performance by exiled Cuban artist, Tania Bruguera, to accuse participants and museum staff of bias. Similarly, Pro-Palestine protestors calling out trustees of the iconic MoMA museum in New York filled and occupied the public space of the museum, forcing its closure to the public. By circulating information via social media, whatsapp, and even a google document featuring an endless dossier of the political leanings of galleries and museums, these artists and activists have proven that their cause hits a deeper and more powerful vein in the art community than we have witnessed in recent memory, directed squarely at our art institutions.

Artwork: Marcella Colavecchio

Censored By: Instagram and Facebook. Source : Don’t Delete Art Gallery

This massive expression of disappointment in spaces that we expect to be the standard-bearers of our history and expression, may also emphasize the probability that we expect too much from them. In many cases, the decisions a museum or gallery makes is influenced not from their own shortcomings, but their own self-censorship as a result of funding needs. Funding, whether private or public, can play a major role in dictating the kind of art we see, and who gets to show it. This kind of censorship is one of the more insidious forms, in that it is not explicitly directed, but encouraged. Lack of funding, threats of withholding funding, and access to funding, are some of the main obstacles to artists’ visibility. This has been especially true in countries where artists rely almost exclusively on public funds and public institutions. These opportunities are drastically influenced by changing governments, who regularly rescind funds and unseat directors of institutions whose programs they do not like, as has swept art institutions of Spain following increasingly conservative elections. This chaotic and unreliable access, along with increasingly crushing financial pressures and lack of legal protections for working artists, have contributed to an environment in which artists and opportunities are extra cautious. In February, the Arts Council of England (ACE) went so far as to publicly announce their review of their funding guidelines to be cautious of funding “overtly political or activist” messages. This kind of backlash against opinions has been forefront in the western world over recent months, as the list continues to grow of artists, professors, creatives, and journalists who have lost jobs and opportunities for expressing their opinions over the Israel/Hamas war.

But, while access to education, opportunities, and funding might always have teetered on uneven ground, the advent of social media and web platforms offered hope for steadier and more equal footing. For over a decade, artists have used the internet to reach new audiences and build careers, as our computers and devices opened windows in to artists’ studios around the world. This optimistic space changed the art world by its ability to shine light into spaces once too far or too dim for audiences to see, and as such we have witnessed brilliant and horrific things, we’ve gathered voices, and even moved bodies countries apart through the power of connection.

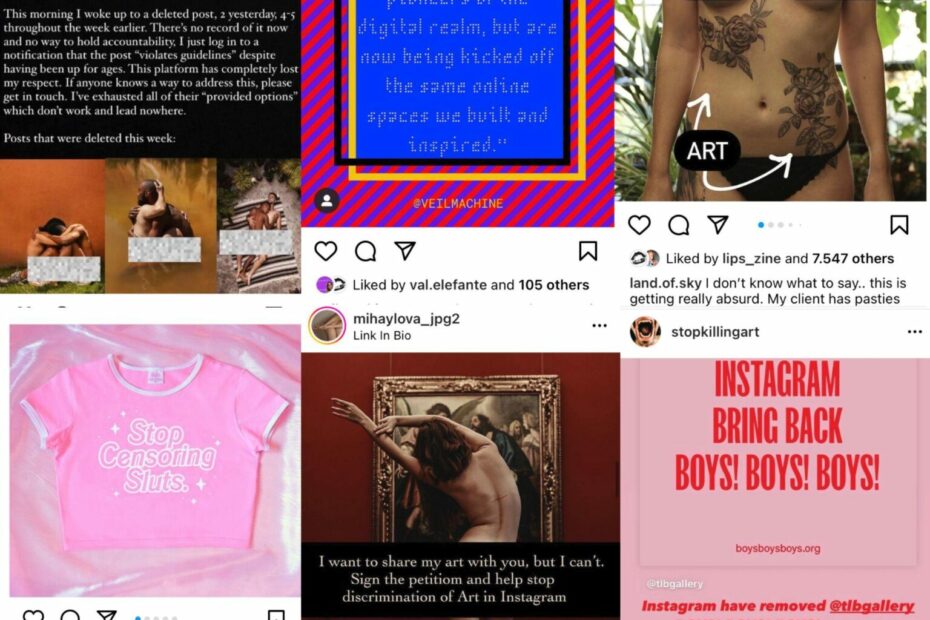

Instagram posts by artists and creatives who face similar obstacles

due to content moderation policies and the implementation of FOSTA-SESTA

But for many artists, that promise of light and connection only illuminated institutionalized biases and left them more vulnerable to censorship and erasure. The internet and social media have increasingly been weaponized against artists and activists in many countries around the world; shut down in times of conflict to stop the spread of information, harnessed to harass minorities, and used to surveil and incriminate dissidents. While these events have been documented, and the subject of anti-censorship campaigns by many human rights and digital rights organizations, there are still other powerful methods of censorship often overlooked, though felt acutely by many artists. Over the years, social media platforms, payment processors, web services, and online marketplaces have erased and censored artists through a steady rhythm of content erasure, suppression, account termination, and manipulation. For many years, these events have been chalked up to ignorant tech companies’ policies, and artists have had very little recourse to correct them. Whats more, the disinterest many platforms have had in listening to artists and protecting artistic expression have laid the groundwork for some worrisome developments, as governments around the world propose increasingly conservative laws that will most certainly have a chilling effect on the freedom of expression of many marginalized groups online. Often in the name of child protection, legislation brought forward by governments in the UK, US, and EU have targeted encryption, privacy, and objectionable content— and set digital rights groups on edge about what this means for our valuable, even life-saving freedoms online. In the US, bills such as The Stop Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) Act, The Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA), and the Eliminating Abusive and Rampant Neglect of Interactive Technologies (“EARN IT”) Act, threaten artists’ ability to share their work, activists’ abilities to communicate securely, and put access to community and art in the hands of partisan politicians. Similarly, the UK recently passed the long-anticipated UK Online Safety Act, which, even after much debate over vague and over-restrictive measures, has many digital rights groups worried over the implications of its proposal to break private communications. Regardless of their stated intentions, the potential negative effects of bills like these are not just hypothetical, as artists online know all too well; implementation of the 2018 FOSTA-SESTA law meant to thwart online sex trafficking instead resulted in bad actors getting better at hiding their actions, while artists became targets for censorship. Countless art images were stripped from social media, accused of “sexual solicitation;” payment platforms began terminating artists’ shop accounts, and other commercial platforms tightened guidelines, resulting lasting damage to many artists. And it is no coincidence that the major movers behind much of these worrisome legislations are notoriously conservative organizations with histories of targeting LGBTQIA communities and sexual freedom.

Instagram posts by artists and creatives who face similar obstacles

due to content moderation policies and the implementation of FOSTA-SESTA

The effect of censorship by erasure and suppression online is exceptionally effective in two ways: it silences the artist by removing their ability to connect and share their experience, and it motivates their future acquiescence in the form of self-censorship. As many artists who have experienced this kind of censorship can attest, this can have dire effects on their finances, prospects, success, and mental health. It can also be very difficult to get anyone who hasn’t experienced it to take it seriously. As such, for years, artists and creatives online who faced these challenges found ally-ships amongst themselves, started online campaigns, signed petitions, and devoted countless hours of unpaid labor to try to effect change. In some cases, they have succeeded – the now-famous “Shadowban” on Instagram had stalked artists on social media for years before efforts from artists and creatives exposed it. But for every artist who has found community among their fellow-censored-artists, there are unknown quantities of artists who disappeared or chose to adapt. Online art censorship has created an entirely new genre of art that has been made with art censorship in mind, with the sole intention of being allowed to exist online. The artists and creatives who have adapted their behavior are exercising the definition of self-censorship, which is the ultimate aim of censorship: the people police themselves. The fight for visibility and opportunity is an increasingly tragic experience for artists who are barred from access and hidden from sight.

In considering Weiwei’s words, it is undeniable that our western society is cracking beneath its veneer of security. As protests, hypocrisy, and censorship bubble to the surface of the art world, the equivocating we have done to swallow our frustration is dissolving as we begin to take our own experience seriously. But we, as a community, must also re-assess our understanding of censorship and suffering to include the less visible, the less obvious threats to artistic expression. To continue to ignore the immense power and importance of our online connections, is to turn our backs on the artists at most risk in our society. Censorship of art doesn’t only exist in the halls of museums or by governmental decree.

Our hopeful belief in an egalitarian internet where all art can be seen has been proven a fallacy, and is at increasing risk for compounding the very censorship many artists are chanting against at gallery doors.

Author: Emma Shapiro

Emma Shapiro is an artist, arts writer, and activist dedicated to advocating for artists facing censorship online. She is Editor-At-Large for Don’t Delete Art, providing resources, support, and education about the state of censorship online for at-risk artists. Passionate about building community and sharing information, Emma founded the international art project and body equality movement Exposure Therapy, and is a regular contributor to publications in the US and UK on the topics of art censorship, digital rights, and feminist issues. Emma has received multiple awards for her artistic and activist work, and has exhibited internationally.

Images : Emma Shapiro & Don’t Delete Art Gallery

https://www.dontdelete.art/gallery/marcella-colavecchio

https://www.dontdelete.art/gallery/sylvie-blum

https://www.dontdelete.art/gallery/spencer-tunick